Colleen Dewhurst won two Tony Awards (nominated eight times) and four Emmys (thirteen nominations) with two Emmys awarded her for two different performances on the same night in 1989, a rare achievement. She is considered by those who saw her on stage over the course of forty years one of America’s great theatre actresses. And though she made a number of films, few of them exploited her talents the way plays could. There were many television roles but almost exclusively as guest stars on dramas and sitcoms. As for the TV movies she appeared in, almost none had her top billed or listed her as number one on the call sheet. On stage, however, Dewhurst was almost always the leading lady; her legacy built on the ephemeral nature of the theatre where performances survive solely in memory. Luckily, what many consider the pinnacle of her stage work—Josie Hogan in Eugene O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten—was preserved on video in a 1975 TV production filmed on a soundstage in Los Angeles. Starring alongside her was her dear friend, Jason Robards. If you’ve never seen it, remedy that. It’s streaming at BroadwayHD.com, but you need a subscription. However, many local libraries might have it on their shelves.

Of her performance in Moon, director, writer and critic Harold Clurman (also an acting teacher and mentor to Dewhurst) wrote of her Josie that “she is of the earth, warm and hearty. She looks and sounds like a woman who can do her own and her father’s work; one, moreover, who possesses the vast sexuality she boasts of, as well as a woman chaste through the very force of that sexuality.” Wow.

Born in 1924 in Montreal, Dewhurst’s father was a former athlete turned shop owner and her mother, a homemaker, and devout Christian Scientist (a religion Dewhurst embraced her whole life). After her parents divorced, she moved at age thirteen to Wisconsin with her mother, later attending Milwaukee Downer College for Young Ladies (“If there was one place I didn’t want to go, it was to an all-girls school,” she told an interviewer in 1986). In her own words, the class clown in her led her to acting, something which she had never given any thought to prior. Married at age twenty-three to an actor James Vickery, they divorced twelve years later.

She also twice married—and twice divorced— the brilliant and highly volatile George C. Scott. They met when he was a last-minute replacement in a 1958 Off-Broadway production of Edwin Justus Mayer's Children of Darkness. A year later, they would play opposite each other as Antony and Cleopatra for producer Joseph Papp’s burgeoning New York Shakespeare Festival, later the Public Theatre. She and Scott had two boys, one of whom, the actor Campbell Scott, played son to his mother on stage in Broadway revivals of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah! Wilderness and Long Day’s Journey into Night.

According to Dewhurst’s obituary in the New York Times, “she once described the twelve years from 1944 to 1956 as desperate and frustrating. ‘It was murder—murder,’ she said. She worked as a receptionist, an elevator operator and on a telephone switchboard between roles in summer stock from Tennessee to Maine and bit parts in New York.”

Slowly, over time and perseverance, she earned the moniker “Queen of Off-Broadway, mainly in classical theatre, to which she owed a great deal to Papp, who cast her as such fierce women as Tamora (Titus Andronicus), Katherine (Taming of the Shrew), Lady Macbeth (Macbeth), Gertrude (Hamlet) and twice as Cleopatra (1959 and 1963). Though she almost always portrayed roles best described as “strong” and “formidable,” Dewhurst confessed in her autobiography that she had come to “hate those two words” as she was simply too good—too versatile to be pigeon-holed in any way. And as for “Queen of Off-Broadway,” she self-deprecatingly wrote that “this title was not necessarily due to my brilliance but rather because most of the plays I was in closed after a run of anywhere from one night to two weeks. I would then move immediately into another.”

In her autobiography, shes waxes rhapsodic about her tenure with Papp’s Central Park Shakespeare productions thusly: “Despite the occasional rainstorm, I had moments playing for Joe outdoors that were magic. I would be standing high on some parapet above the stage, not speaking for several minutes, looking out over the trees into the sky. With the wind blowing and the clouds sailing past the moon, I had no sense of time or that I was in the middle of one of the world’s largest cities. Nothing around you tells you where you are but, somehow, perhaps because you’re in the middle of this play, you feel safe. Nothing can touch you; whatever your reality is outside of the theatre just disappears. In those moments, I somehow felt quiet and at one with everything around me and had the greatest sense of peace I have ever experienced. I’ve never had that feeling on any stage except at the Delacorte in Central Park.”

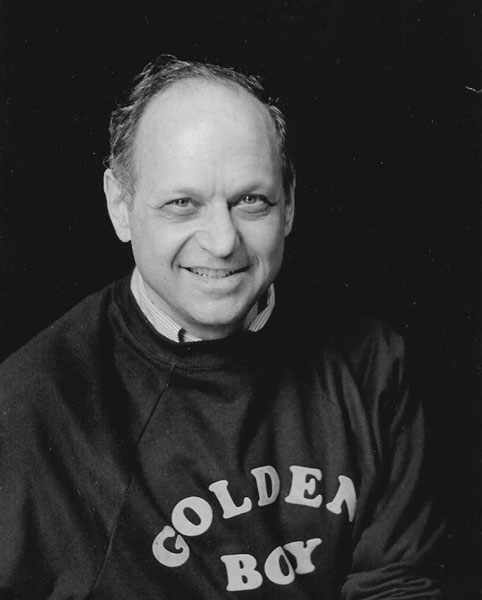

I was fortunate to have begun seeing Dewhurst in plays as far back as 1970, when during my teenage theatregoing years, I fell for her in a revival of Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Woman of Setzuan at Lincoln Center. In the dual roles of the female Shen Te and Mr. Shui-Ta, a businessman she masquerades, I was mesmerized. I genuinely liked the production, only to find out years later when Dewhurst wrote about it that it was one she particularly loathed. Of course, none of that mattered when she welcomed me, a thirteen-year-old, into her dressing room when I visited her backstage. Gob smacked by her presence, what I remember most was that she was taller than I was, that her million-watt, incandescent smile never dimmed, and that we had quite a conversation.

Finally, as was my wont back then, I asked for an autograph. She seemed momentarily disappointed but relented. While signing, without looking up she said, “You know, I really should be asking you for yours.” This was both charming and disarming and kind of did the trick. I never asked anyone for their autograph the rest of my life.

An activist, Dewhurst lent her voice early in the fight when the AIDS epidemic was wiping out members of the theatrical community at a devastating rate. She helped pioneer the formation of the Equity Fights AIDS Committee, which merged with Broadway Cares in 1992 to become Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, lent her voice to a variety of women’s issues such as the peace movement, and served as President of Performing Artists for Nuclear Disarmament. She also was a two-term President of Actors’ Equity between 1985 and her death in 1991, where she made great strides for union members’ rights, even if some of the issues she was addressing are still searching for remedies. In a 1986 interview with the Los Angeles Times (thirty-five years ago, mind you), she spoke of the so-called “non-traditional” casting of actors in roles without regard to race or gender. “We are not now representing society as it now exists… especially true when casting the classics. And this is one area where the theatre could take the lead, because art is supposed to represent life. At least, we could send a message, and if the audience doesn’t like it, they can walk out (of the theatre).”

In 1982, when the Morosco, Helen Hayes and Bijou theaters were being torn down for a hotel, Dewhurst was on the barricades leading protests against their destruction. I’ve always found this photo of her pained cry that made the front page of the New York Times to convey everything the community felt when those theatres came down.

Of all the Broadway plays I saw Dewhurst in, the most memorable was a 1977 production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? directed by Edward Albee himself. Playing opposite Ben Gazzara, who matched her blow for blow, I left a Wednesday matinee performance energized by three hours of pure theatre. Her smoky cigarette-induced delivery of Martha’s “I don’t bray!” was vocalized to sheer perfection.

This photo reminded me of those jeans, that sweater and her bare feet like it was yesterday. Sadly, those cigarettes took their toll. Dewhurst died of cancer thirty years ago this week (August 22nd) at age sixty-seven. Her companion for nearly twenty years was Ken Marsolais, a theatrical producer, who she met when he was an assistant stage manager on A Moon for the Misbegotten.

After her death, Joe Papp summed it up simply and beautifully about her life as both actress and activist. “She was socially conscious. She loved people. You don’t have to be a great person to be a great actor, but she happened to combine both.”

In 1974, when she received her Tony Award for Best Actress for Moon, it was oddly the first show she’d ever been in that was a critical and financial success. She was fifty years old. For my money, her speech is one of the great ones ever given at an awards ceremony. Please watch it at the 2 hour and 16 minute mark. It does not disappoint.

Then again, neither did Colleen Dewhurst.

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. Also, please follow me here on Scrollstack and feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...