Even after all these years, whenever I watch James Cagney as George M. Cohan in Yankee Doodle Dandy (usually on July 4th when it airs annually on Turner Classic Movies ), it’s always startling when late in the film he sings and dances while playing Franklin Roosevelt. As part of the biography the film depicts, it shows Cohan in the Broadway production of the Richard Rodgers & Larry Hart/George S. Kaufman & Moss Hart musical I’d Rather Be Right, which opened eighty-four years ago tonight. Startling, because the majority of Americans have come to know that the man who was President longer than anyone else (elected to four terms), was a paraplegic. After all, the statue at the entrance to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C. has him seated in his wheelchair.

But this is now and that was then. While he was President, Roosevelt’s disability was something he was keen on concealing, which he managed to do throughout his political life. He was aided by a world press with little interest in outing the President of the United States as someone who couldn’t walk, something impossible to imagine today. Out of all the film footage that exits of one of the most photographed leaders of the 20th century, there are only 30-40 seconds that show Roosevelt walking. The ploy, developed by Roosevelt himself, involved wearing heavy iron braces; then his using a cane to lean hard on the arm of someone very strong so that he could pull off the stunt. This ploy, or his “splendid deception,” as it came to be known after the fact, was due to the polio that had robbed Roosevelt of the use of his legs. But most Americans were unaware of that. It was thought it was merely difficult for him to get around, or that he might be “lame,” a term now well retired.

Which is why movie audiences in 1942 weren't put off seeing someone as Roosevelt (then in the ninth year of his twelve-year presidency) doing a buck-and-wing. The same went for audiences five years earlier when I’d Rather Be Right opened on Broadway. Even with FDR as a character, its interest was less political than fanciful; a frothy musical comedy. Playwright George S. Kaufman (with co-writer Morrie Ryskind and the Gershwin brothers) had six years earlier created the political satire Of Thee I Sing, the first musical to nab the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. For I'd Rather Be Right, Kaufman enlisted his old playwriting partner Moss Hart for a story that begins innocently enough in Central Park, where a young couple become involved with the President, who they casually meet one evening when he happens to be out all by himself for a stroll (yeah, right). You see, the boy is unemployed and wants to marry his girl, and they need Roosevelt to fix the economy so he can get a job!

George M. Cohan had once been the dominant force on Broadway for nearly three decades in the early part of the century. Not only did he write the book, music and lyrics to all his shows, but he often performed the starring role as well. He also took credit for staging many of them — and he was not modest or nice about any of it, possessed as he was of an outsized ego. By the time of I’d Rather Be Right in 1937, Cohan had been in near semi-retirement, which was NOT a personal choice. The old fashioned stylings of the plays and musicals he wrote fell out of favor, and no one was willing to hire him to write or star in their shows, because … well, why would they? Since he had always been the boss, every producer, director, playwright and composer-lyricist team in town knew what they’d be in for with Cohan on board. A collaborator, he was not.

And on I’d Rather Be Right, by all accounts, Cohan stayed true to form. He already bared ill will towards Rodgers and Hart, who had written the score to the 1932 film he starred in called The Phantom President. He hated the team on sight, mainly because he was angry that he had been put out to pasture in favor of the more literate and sophisticated Broadway fare that Rodgers & Hart helped to create. It had been nine years since a Broadway musical of his had been produced and Cohan intensely felt that sting of unemployment. According to theatre historian Ethan Mordden in his book Sing For Your Supper: The Broadway Musical in the 1930s, Cohan belittled the songwriters behind their backs calling them “Gilbert & Sullivan." He even re-wrote Hart's lyrics in the song "Off the Record" during the Boston tryout and performed them on stage before being read the riot act.

But Cohan was perfect casting for Roosevelt, and it provided a comeback of sorts, that Sam H. Harris, the wily producer of I’d Rather Be Right, was correct to exploit. The critics enjoyed the show, even though it was mild satire and somewhat low-echelon Rodgers & Hart. It produced one standard, “Have You Met Miss Jones?”, but no other songs of any distinction. Again, in the witty wordplay of Ethan Mordden, “The show isn’t Boy Meets Girl. It’s Boy Meets President and Asks Him To Balance the Budget.”

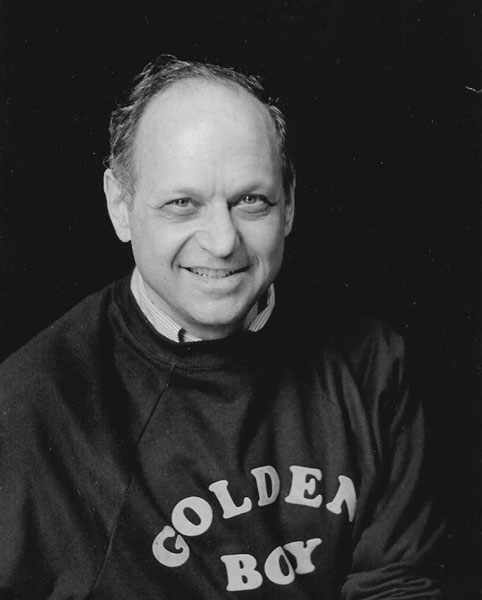

In a promotional film, produced at the time of the original production, here is some rare footage that gives something of the idea of how charismatic Cohan was in the role.

Of course, it would be remiss to not include Cagney performing as FDR with Rodgers & Hart’s “Off the Record," which includes some updated lyrics to insult Hitler, as Yankee Doodle Dandy was released just six months after the United States entered World War II.

I’d Rather Be Right was a crowd pleaser, playing for 290 performances, which was a long run in its day. But that wasn’t enough for Cohan. He had to prove he could still do it all as in the old days. So two years after his final performance as Roosevelt, he returned to Broadway in The Return of the Vagabond, a melodrama he wrote, produced and starred in.

It ran one week.

After that, Cohan retired for good, and passed away two years later, five months after Yankee Doodle Dandy premiered. This meant that not only did he live to see his story become the number one grossing movie in America, but he got to serve as a consultant on the film. In that capacity, Cohan stated in print that he was pleased with Jimmy Cagney’s performance (though we’ll never know what he REALLY thought since he was getting paid to say it). Cohan had personally expressed his wishes earlier that Fred Astaire play him in the film. All of which prompts my personal guess that even with Cagney winning the Oscar for playing him, George M. Cohan would just as soon rather been right.

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. Also, follow me here on Scrollstack and feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...