Looking back on my teenage theatergoing heyday, which occurred between the years 1969 and 1972, even fifty years later, the memories remain fresh and intact. From the ages of twelve to sixteen, often solely on my own, I attended 200 Broadway shows over a four-year span. I covered the costs entirely with my own money, too, earned from my paper route delivering Newsday, "the Long Island newspaper." And, yes, at the risk of repeating for those who've heard me mention it before — all at the average cost of $3 a ticket. It's chronicled in my book Up in the Cheap Seats, which tells the stories of an obsessed teenager, eagerly getting an education sadly unaffordable to a kid — or anybody today for that matter — with a shared passion like mine.

At this time of good cheer in December in New York City, and with the theatre only recently having returned from the forced and extended pandemic break, I thought I would reflect on what was going on back in the day, a wildly different era, especially by way of the look and feel of Times Square fifty years ago.

Richard Nixon was in his first term as President, the Vietnam war was still raging, unrest in India and Ireland were on the front pages every day, and here in New York City, the subway was going to go up to 35 cents in January 1972. The #1 film in America was Sean Connery's return as James Bond in Diamonds Are Forever and the biggest selling single (remember those?) was "Family Affair" from Sly and the Family Stone (what, you don't remember them either?). As for television, if you guessed it was most probably a CBS show, you'd be right. It was the brilliant All in the Family, which premiered in January of '71 and had skyrocketed to number one status almost immediately.

During this wild and wonderful week fifty years ago in December 1971, a new Broadway musical Wild and Wonderful opened. Its plot concerned a former West Point cadet sent by the CIA to infiltrate a gang of anti-war types. It opened at the Lyceum on December 7th and, in true Pearl Harbor fashion, sunk after a single performance (despite future Broadway legend Ann Reinking in its ensemble). She would have better luck on her next musical, Pippin, the following season.

Andrew Lloyd Webber's very first Broadway musical, Jesus Christ Superstar, had opened in October to strong business. The first time a concept album had been turned into a full-fledged theatre piece on Broadway. Critics may have been rough on director Tom O'Horgan's over-the-top production, but audiences enjoyed it, since by the time of its opening the album had already sold over 3.5 million copies. Other concept musicals derived in similar fashions over the years, include Webber's own Evita, with lyrics by his Superstar partner, Tim Rice, indelibly staged by Harold Prince; The Who's Tommy, and the current Tony Award winning Best Musical Hadestown, which began life as a concept album eleven years ago with music and lyrics by Anaïs Mitchell.

The lowest price in 1971 to see a show was $2 (that's all I paid to see Company with its original cast the week it opened), while the top ticket price only went as high as $15 for the best orchestra seat. The biggest sellout was the revival of the ancient musical comedy No, No Nanette (first produced on Broadway nearly 100 years ago in 1925). Another nostalgia-filled musical, Follies, was also playing, but selling nowhere near as well as Nanette. Seven months into its eventual 15-month run, Follies was a very different animal than Nanette, challenging audiences in ways that made a good many uncomfortable (and a good many left feeling they were witnessing the greatest musical ever produced).

With no TKTS tickets booth installed yet in Times Square, tickets were only sold at the box office or by mail (I did both). Not being tall, I barely came up to the window, but the personnel were always kind to me and treated me like an adult. Naturally, I'm sure I had them laughing with my use of as much theatre lingo as I could muster, such as "I'm looking for a single for the matinee?"

And get this: since Follies wasn't a sellout, and with no TKTS booth to at least assure producers that they could sell seats even if it meant lower prices, discount coupons were available instead to shows that weren't doing so great. These were called "twofers" (basically allowing "two for" one) and they made theatre affordable for thousands of students and seniors. Imagine being able to sit in the 13th row of the orchestra for as little as $5 and see Follies! And if you turn your head sideways at the twofer below, here’s proof you could have seen The Rothschilds for the same price.

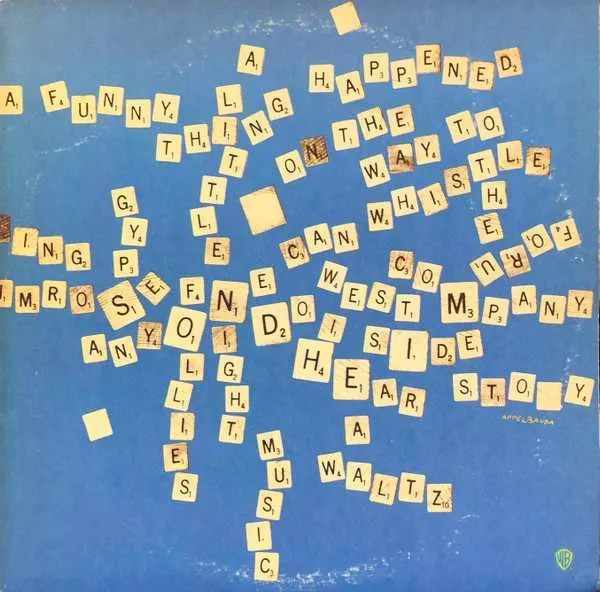

The nostalgia factor with No, No Nanette, which was catering to mostly older (and white) audiences, was also reflected in replacement casting on and off Broadway. At age seventy-two, Gloria Swanson (of Sunset Boulevard fame) was the final actress to play the meddling mother in Leonard Gershe's comedy hit Butterflies Are Free, a holdover from the 1970 season. A staple of Warner Bros. musicals of the 1930s, Joan Blondell was playing the harridan mother in the year's Pulitzer Prize winner paul Zindel’s The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds, at the now demolished New Theatre on East 54th Street. And to replace the irreplaceable Lauren Bacall in Applause, the 1970 Tony Award winner for Best Musical, the producers went for an irresistible All About Eve connection (the musical was based on it), by casting Anne Baxter as Margo Channing. Having once portrayed the young Eve in the 1950 film (same year as Sunset Boulevard, come to think of it), it was a natural fit. Vivian Blaine, the Tony Award winning Miss Adelaide of the original Guys and Dolls (also 1950), was brought in to sing "The Ladies Who Lunch" towards the end of the run of Stephen Sondheim's groundbreaking Company (closing on New Years' Day 1972 after a run of about twenty months). I got to see Blaine when she did it the following summer at the Westbury Music Fair on Long Island, a theatre-in-the-round that got its fair share of stars over the years in great musicals (it's where I saw Zero Mostel recreate his Pseudolous in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum as well).

Holdovers from previous seasons (in addition to Company) were Hair (1968), 1776 (1969) and the grandaddy of them all Fiddler on the Roof (1964). Hello, Dolly! which had opened earlier the same year as Fiddler, had closed in December 1970. Over the next summer, the denizens of Anatevka would overtake the citizens of Yonkers to become not only the longest running musical in Broadway history, but stick around close to another year and become the longest running show of all time, surpassing Life with Father's record-breaking seven-and-a-half year run. However, what no one could have predicted back then was that Oh, Calcutta!, after a two-year stay on Broadway, would return in 1976 and play a much smaller house (the Edison Theatre, now defunct on West 47th Street) where it stayed for an additional twelve years!

An ad for a play in the Sunday Arts and Leisure section of the New York Times for this week fifty years ago was David Rabe's Sticks and Bones, then playing downtown at the Public Theatre in the East Village. Its founder, Joe Papp, had already moved a musical that had played in Central Park over the summer to the St. James Theatre, and when springtime came around, he arranged to move Sticks and Bones uptown as well. He triumphed at that year's Tony Awards and collected (as producer) Tonys for Best Play and Best Musical. The musical was Two Gentlemen of Verona, a contemporary update of a relatively minor Shakespeare comedy that was given a fresh and boisterous production with music by Galt MacDermot (Hair) and lyrics co-written by not only Shakespeare (at times) but by its director Mel Shapiro and a thirty-three-year old playwright named John Guare, who had already had great success earlier in the year with off-Broadway's The House of Blue Leaves, now considered a classic American comedy.

And in terms of coming full circle, last night saw the opening of the third Broadway revival of Company since its premiere in 1970. It comes on the heels of the sudden death of Stephen Sondheim, who basically owned the seventies in terms of what he and Harold Prince accomplished in that decade. There should always be a spot reserved at a Broadway theatre for a show that finds new fans with each successive revival and, as this one does, break new ground. Flipping the gender of its protagonist is just one among a number of bold and exciting changes that resulted in this new Company getting glowing reviews online this morning (save the New York Times, which was in a distinct minority). Sondheim knew better than anyone that an artist must change in order to grow, something he never stopped doing in his nine decades on earth. It’s a shame he didn’t live to see his trust in that vindicated by these ecstatic reviews.

Obviously, the theatre is much different from what it was fifty years ago with a mix of changes for the good and the not so good. For me, I remain as optimistic as I've always been about what lies ahead... though it sure would be nice if ticket prices didn't force people to take out second mortgages so they can take the family to The Music Man.

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. Also, follow me here on Scrollstack and feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...