July 27, 2020: Theatre Yesterday and Today

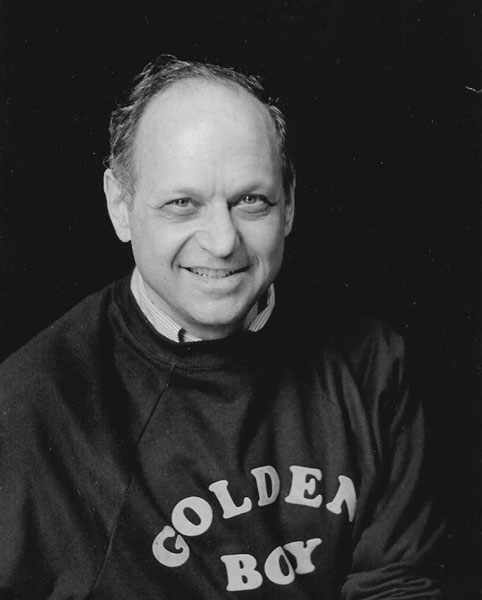

Legendary comedian Bob Hope passed away on this date in 2003, just two months beyond his 100th birthday. Although still known to millions at the time of his death, a new generation of young people most probably read his obit with little awareness of the tremendous impact he had on American culture. And now that it's seventeen years later, we're close to another generation very possibly unfamiliar with Hope and exactly what made his contributions to the entertainment industry so important. For one thing, Hope single-handedly invented the notion of a “stand-up” comic on television, as well as coming to embody what it meant to elegantly and wittily host an awards program on television. Now with laughter a much-needed commodity, it's time to take a look back when Hope was king.

My first exposure to Hope was exactly in that capacity—as host of the annual Academy Awards when I first began watching them as a little boy in 1966 (when The Sound of Music took home Best Picture). Hope was well versed in such appearances (his first time hosting was in 1939 and his last in 1977). Making additional appearances at other Oscar ceremonies well into the late 1980's, he still holds the record for hosting the broadcast 19 times, a feat unlikely ever to be beaten (and for the record, Billy Crystal, a different host to a different generation, is in second place with nine times).

Throughout the 1940s, Hope was as big movie star as there was in that highly competitive decade. His teaming with the actor-singer Bing Crosby in seven Road To… pictures over a twenty-year span helped launch the “buddy film” into popularity, still a reliable box office genre today. But before translating his fame onto the big screen, Hope sang and hoofed his way through vaudeville which led the way to his becoming a Broadway star. He was also one of radio's great personalities, and once television eclipsed that medium as the primary entertainment for most Americans, Hope’s TV specials numbered in the dozens well into the 1970s. But the place where Hope’s talents were nurtured was on the stage, as mentioned first in vaudeville, and then on Broadway. Unfortunately, once he headed out to Hollywood in 1937 after he appeared in Cole Porter’s Red, Hot and Blue (co-starring with Ethel Merman and Jimmy Durante) he never did another musical on stage.

It always surprised me as a kid when I would suddenly see Bob Hope sing or dance. It wasn’t that he did it competently, as if he were being asked to do something out of his range of expertise and acquitted himself nicely. No, he was really, really good. It was like the way it always seemed strange to see James Cagney dance (for dance strangely, he did), since my primary means of identifying his talents originally was as a tough guy or gangster. Like Hope, he began first as a song and dance man and nothing delighted me more than the first time I saw the film The Seven Little Foys which featured them both. This was a 1955 film that starred Hope as Eddie Foy Sr., a vaudevillian who performed with his children on stage. Cagney has a cameo, repeating his Academy Award winning performance as George M. Cohan from Yankee Doodle Dandy. Here’s the dance they do together which never fails to delight me every time I see it (and I have seen it countless times).

It was Broadway’s loss and Hollywood’s gain when the theatre lost Hope to movies forever. He really had a peculiar knack for singing and dancing, which were rarely utilized once his on-screen persona of the cowardly comedian took hold in the 1940s. Woody Allen has claimed time and again that Hope was among his favorite comedians, and the early Allen characters in films like Take the Money and Run and Bananas owe a great deal to Hope. But again, if you watch this clip from his first Hollywood film, The Big Broadcast of 1938, his performance with Shirley Ross is exquisite. It gave him his signature song, “Thanks for the Memories,” which he would sing with specialty lyrics for the next seventy years rewritten for just about any occasion (Hope liked making money and would show up to open a car wash if his price was met), but it sadly diluted his brand. Watching the original though is enough to take one’s breath away. Take in how tender and well-acted it is, never more so than Hope’s action with the glass, the swizzle stick and the piece of fruit. It’s masterful.

Hope is in The Guinness Book of World Records as being the most awarded entertainer of all time (over 1,500 awards) and for holding the longest contract with any TV network (a “lifetime contract” that was finally dissolved after sixty-one years). On that occasion, Hope quipped that he had “decided to become a free agent.” He was ninety-three-years-old.

Hope died at his home of sixty-four years in Toluca Lake, California, less than two miles from NBC where he taped so many of his TV specials. It has been widely quoted that on his deathbed, when asked where he wanted to be buried, Hope told his wife, “Surprise me.” I don’t buy that story for a minute for a number of reasons (who asks that of a multi-millionaire who certainly had a long-standing will in place?), but it sounds like something Hope would have said. All of which brings to mind the great line from the John Ford film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

And one fact is for sure: Bob Hope was a legend.

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. Also sign up to follow me here, and feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org

Write a comment ...