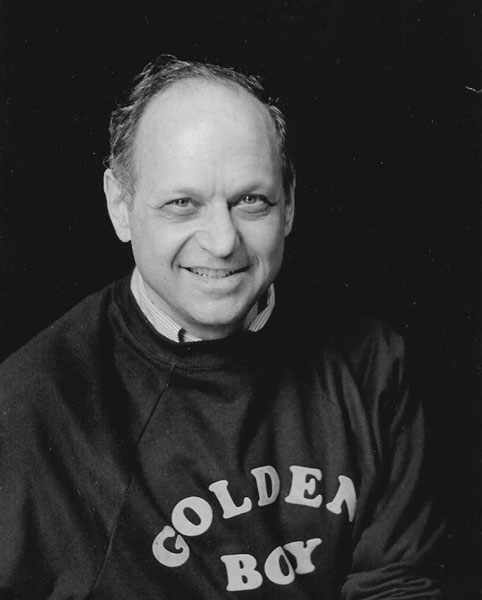

I'm re-running this column from four years ago to honor the 85th birthday of Jerry Orbach (born October 20, 1935). One of the highest compliments I've ever received was when shortly after posting it, I got an email from Chris Orbach (who I don't know) and who wrote: "You captured my dad perfectly." You can read all about this beloved actor in today's "Theatre Yesterday and Today."

Was there anyone more well-liked in the Broadway community than Jerry Orbach? I’ll go further and include the film and television community. Hell, how about the entire community of New York City? The stories of police men and women calling out to him on their street beats and out of patrol cars, in deference to his longtime portrayal of Detective Lennie Briscoe on Law & Order, attest to both his likability and approachability.

Born in the Bronx on this day, Jerome Orbach was the son of Leon and Lexy Orbach, both of whom had brief flirtations with show business. His dad had been a stringer in vaudeville and his mother a radio singer. While in the seventh grade, the family moved to Waukegan, Illinois where Orbach attended high school, then onto the University of Illinois. Staying only a year, he transferred to Northwestern in Evanston, where its prestigious drama department was renowned. He left before earning his degree due to the stage work that was coming his way after proving his versatility in summer stock. He would later claim that his days in stock helped him to control his voice and "not to do too much with my eyebrows."

He was fortunate to be cast in the role of the Street Singer in one of the biggest Off-Broadway hits of all-time: a revival of The Threepenny Opera that starred its composer Kurt Weill's widow, Lotte Lenya, in the role she had created in its original German production. Opening with it in 1955, he stayed three years, eventually taking over the lead role of Mack the Knife. Orbach was that rare breed of actor who had no problem sticking with a show for years at a time. Most leading actors with an eye on getting stale, hardly ever extended their contracts beyond a year. Orbach was the opposite and a throwback to actors of yore. It applied to his first starring role on Broadway in the musical Carnival, which he stayed with from opening night till closing, almost two years later. With Chicago, he stayed for two years, and, in 42nd Street, for three. It earned him the reputation as a stalwart, as well as a genuine leader whenever he was entrusted with the star status of a given company.

I never met him, but I admired him so much. I remember waiting by the stage door after I saw him in Promises, Promises back in 1969, but he never came out, which is common for some actors between a matinee and evening performance. Reading the review I wrote when I got home that day, from a twelve-year-old’s perspective it doesn’t appear I took it out on him: “Jerry Orbach is a musical comedy genius, as well as one of the finest actors around.”

Proof of that came when he won the Tony Award that spring for Promises, sharing the evening in the company of his fellow actors in this photo below. It was on this night that James Earl Jones won for The Great White Hope, the first of his first two Tonys; Julie Harris took home #3 for Forty Carats and Angela Lansbury sported win #2 for Dear World. Between the four of them, they would eventually be honored with 14 Tony Awards. Good company, indeed.

Anita Gillette, who co-starred with Orbach in a 1966 City Center two-week engagement of Guys and Dolls, told me that for the rest of his life, that whenever Orbach phoned her, he would never say hello, but would warble the first few bars of “I’ll Know,” the ballad they once shared on stage together.

Strangely enough, there was one occasion where I thought I would finally get the chance to meet this actor whom I’d admired from such a young age. This was in 1980 at the closing night party for a play that I was understudying in on Broadway, a fiasco called Censored Scenes from King Kong. Never heard of it? Well, there’s a reason for that. Anyway, I was told to go to an address in Chelsea for a small party where the company was going to go and commiserate, and that it was Jerry Orbach’s brownstone. Great! Only Jerry Orbach wasn’t there. Nor was Mrs. Orbach. To this day, I don’t know the set of circumstances, but with all his stuff around, I can assure you it was definitely his place.

During my teenage years I saw him in 6 Rms Riv Vu (classified ad-talk for Six Rooms, River View), opposite Jane Alexander. Both were a lot better than what playwright Bob Randall wrote for them in this minor comedy, though it was hardly a waste of time to enjoy these two professionals fall in love on stage. The next time I saw Orbach, was in 1975 as Billy Flynn in the original Broadway production of John Kander and Fred Ebb and Bob Fosse’s Chicago. I saw him play this role three times (well, two and a half — I second acted the show on one occasion). He was so in command, and so at ease (really his greatest virtue), that it felt as if when Jerry Orbach was in a musical you could easily relax, safe that for the next two hours all would be right with the world.

My last time (and everyone’s, as would turn out to be the case) to see Orbach create a role in a stage musical was when the 1930’s Warner Brothers musical 42nd Street was re-done for Broadway in 1980. I caught it the week it opened, which turned out to be one of the most turbulent in theatre history, what with the drama surrounding the death from a rare blood cancer of its director and choreographer, Gower Champion, on the show’s opening night. That its producer David Merrick, somehow managed to withhold this information which had occurred earlier in the day from the entire New York press (as well as his cast and company), all playing directly into the showman’s hands. Grimly announcing the news from the stage after the musical’s wildly receptive ovation at its opening night curtain call, the photo of Merrick surrounded by his stunned cast made the front pages of every newspaper in the world.

After a full five-minute ovation, “the cast, still assembled on stage, seemed as startled as the audience when Merrick came out on stage,” as reported in the Washington Post. “When he [Merrick] began speaking, saying “This is a very tragic occasion for me,” some in the audience chuckled, apparently suspecting a joke. But when he said that Mr. Champion had died, there were gasps and screams. Merrick embraced actress Wanda Richert, a young star of the show, who was weeping. The audience began to file out silently.”

The whole event was such a shocker that it felt as if it had been pre-planned, which it had. But even Merrick didn’t quite know how to handle things once he made the announcement. It was Orbach, in his role as the show’s director, who had the strength of mind to call out for the curtain be lowered, affording the cast the privacy to take in the devastating news, rather than in front of the thousand-plus crowd.

And for those who don’t remember, “Try to Remember,” the title of this piece, refers to the song by Harvey Schmidt and Tom Jones from The Fantasticks, which was introduced by Orbach as the original El Gallo when the show opened its historic run at the Sullivan Street Playhouse. Though Orbach moved on, The Fantasticks stayed put without interruption at the tiny 99-seat theatre for forty-two years.

Of course, he'll always be Jennifer Grey's devoted dad in the 1987 film Dirty Dancing ("Nobody puts baby in the corner"), as well as the glorious Lumiere the Candlestick in Beauty and the Beast (1991). But for my money, his greatest film performance is as Martin Landau's brother in Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors. If you've never seen him play this taciturn, low-level gangster, it's a lesson in character built upon something very real from deep within Orbach's knowledge of how the real world works.

One final illustration of the sort of guy Orbach was, as opposed to being just a wonderful actor, is a story told by his Law & Order co-star, S. Epatha Merkerson. After his death, she told the New York Post how “people adored him,” and recalled that one day while sharing lunch with Orbach and co-star Benjamin Bratt, how several fans approached the table. “Jerry stopped eating to talk to them. But after a while, I whispered to him, ‘Your food is getting cold.’

“‘Kid,’ he replied with a big smile, ‘these are the people that keep us going!’”

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. And please feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...