Joe Allen was a unique and indelible part of the Broadway theatre community by way of the restaurants he owned and the people he served for more than fifty years, many of whom were devoted to the oasis his watering holes provided. This tribute is direct from the chapter in my book Up in the Cheap Seats about a 1972 musical called Dude, and titled “The Bomb.” This had to do with the coincidence that Joe Allen could easily have pulled off the moniker of “the Dude ” (he was very cool) and his establishment is, in modern parlance, “the bomb.”

The self -named Joe Allen restaurant has held the same spot on West 46th Street in the theatre district for more than fifty years. A chief reason for this, besides doing a good business, is that Mr. Allen need never fear eviction: he owns the property and is his own landlord.

It is also his home — he lives right above his long - successful establishment.

Allen bought the brownstone that houses his restaurant in 1965 (from Fred Trump, as it happened) at a time when the street between 8th and 9th Avenues was “red-lined. ”

When Allen mentioned that term to me in an interview I conducted with him in 2014 I had to ask what it meant. He explained that the street was so undesirable that no bank would loan money towards the purchase of any property there. It was cons idered worthless.

With help from some friends as investors, Allen was able to buy two of the buildings — one for $75,000 and the other for $80,000 — before adding a third a short time later. This trio of townhouses now has a market value roughly in the neighbo rhood of at least $20,000,000 (a very nice neighborhood ).

The street, designated as “Restaurant Row” in 1973 by the City of New York, offers more than thirty eateries — three of which (Joe Allen, Orso and Bar Centrale) are Allen’s.

And it all began with one m an and a vision.

Allen’s init ial goal was to attract working - class members of the theatre community, as opposed to its sta rs, and create a safe haven that was cheap and comfortable . This meant young (and sometimes not so young) struggling actors, chorus people, stagehands and everyone else “trying to scr atch out a pleasant simple tune without breaking their necks . ” It wasn’t easy. As Allen tells it: “ Nobody had any money. In an effo rt to seduce chorus people, I said, ‘Go ahead and sign for it.’ Everybody paid — they could be slow, but they all paid, because they had to be able to come in here to see their friends.”

This proved a smart template . Eventually Allen would cater to the biggest stars on Broadway, mindful of keeping things low - key enough to also make a humble , starving artist feel welcome. To this day, prior to a matinee or evening show, tourists enjoy its juicy burgers or its famous banana cream pie. Later, after 10:00 p.m. , when the theatre district sidewalks fill with folks getting out o f shows, Joe’s is home to more than the tourists . It is a communal place to unwind after a performance until the food and drink stop being served and the waiters gently urge customers to go to their real homes. Whenever I came to New York during the thirty years I lived in Los Angeles, I would visit Joe Allen and always find a familiar face there (besides Mr. Allen’s).

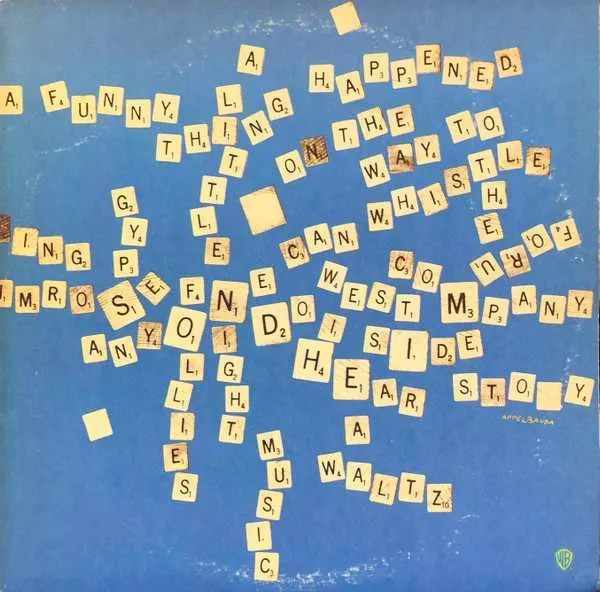

Upon entering the restaurant, one of the first things likely to be noticed are the walls of framed posters, or window cards, as they are referred to in the trade . These provide a “who’s who” and “what’s what” of the worst flops ever produced on Broadway.

They also reflect an insider’s sense of humor that makes the place feel like somewhere it would be wise not to take yours elf too seriously. Have a drink, relax and enjoy the fact you may be in a hit (for now) because tomorrow the poster of your latest failure could be on the “Wall of Shame” for a ll the world to see . It began, Allen has said, as a joke.

After Kelly, a notorious 1965 failure of a musical that had the distinction of closing on its opening night, someone gave him the poster to hang up, sort of as a gag. Who would think of putting up a bomb to remind people of how failure is more common than success in the theatre business? Well, Joe would. And it wasn't long before someone gave him the poster for the musical version of Truman Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's, which unlike Kelly, didn't even make it to its opening night. In spite of being headlined by two of the brightest young stars on television back in 1966—Mary Tyler Moore and Richard Chamberlain—its volatile producer, David Merrick, took out an ad in the New York Times to announce he was shutting down the production while still in previews, “rather than subject the drama critics and the public to an excruciatingly boring evening.”

After those two posters went up, Allen would hear from a producer who would plead to him. As he tells it: “Please don’t put up any of my flop posters” and I’d say OK... then, three months later I’d hear, ‘Could you put the poster up?’ They suddenly realized that the poster is all that will be remembered.”

I wrote all that five years ago. Today, we're living in a world where Joe Allen, Orso and Bar Centrale are all closed due to the pandemic. And as for the "Wall of Shame," I feel even more pride than ever over my having had the fortune/misfortune of seeing a good number of the more than three dozen posters that adorn the walls of Joe Allen . I think it has to do with how we all have to work through and survive disaster, which is as important a lesson of Covid that there can be. Failure is as much a part of life as success, whether you're on the stage or in the audience, and Joe understood that on some instinctual level.

And with partial lock downs still here a month shy of a year, there's nothing I want to do more than return to West 46th Street after seeing a show and have a drink and see friends. And on that first night when Broadway does eventually reopen, there is no doubt I will see a show and make it to Joe Allen afterwards for the tasty meatloaf, as well as a martini poured into that tiny vial the way the boss expressly dictated. And my first toast will be to Joe himself.

But let's leave the final word to Joe, who after a lifetime spent in the restaurant business, summed it all up once by saying: “Life is a cruel joke. But less cruel and more of a joke when you’re in a good bar.”

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. And please feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...