November 18, 2024: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler.

There used to be a certain subset of actor expert in comedy, or boulevard comedy as it was once called. They were indispensable in what is now a bygone era of Broadway. Coined by the French as comedie de boulevard (or a comedy of the street), it generally translates as “light comedy.” With today’s audiences demanding much more for their money and with prices rising every season, it’s no wonder plays of this ilk are almost extinct. With the invention of the sitcom in the 1950s, one-set plays became free to anyone with a television. It has been many decades since something like 1943’s The Voice of the Turtle, by John Van Druten, a classic example of this genre, could run on Broadway for close to four years.

As its roots are French, there’s no better example of a Broadway comedie de boulevard than Cactus Flower (1965). Pierre Barillet and Jean-Pierre Gredy’s play that first premiered in Paris, later adapted and directed for Broadway by Abe Burrows. Running for three years, producer David Merrick signed his star Lauren Bacall to a two-year contract, resulting in her playing it for 2/3rds of that time (she came to hate him for holding her to the commitment).

Before the rave reviews in New York, there was trouble out of town during Cactus Flower’s Philadelphia tryout. The leading man was Joseph Campanella, a square-jawed leading man-type with hundreds of hours of television work on his resume. Sadly, he was outmatched playing the love interest against a force such as Bacall. The role begged for a light comedian; someone Bacall could engage with that would keep the sexual tension high and the dialogue floating like rich cream in coffee. After its first performance, it was clear things were curdling.

In Philly that night, Merrick entered Bacall’s dressing room and told her, “You were great, but I’m going to replace Campanella.” Though shocked, Bacall understood. “I felt sorry for him—one performance was no test, yet I suspected David was right,” she wrote in her autobiography, By Myself. “He had been miscast.” As Burrows put it in his autobiography, Honest Abe, “Joe was a very good actor and a very nice man but he just wasn’t happy in a farce. At least he didn’t suffer any financial loss because he had a contract and David Merrick honored it.”

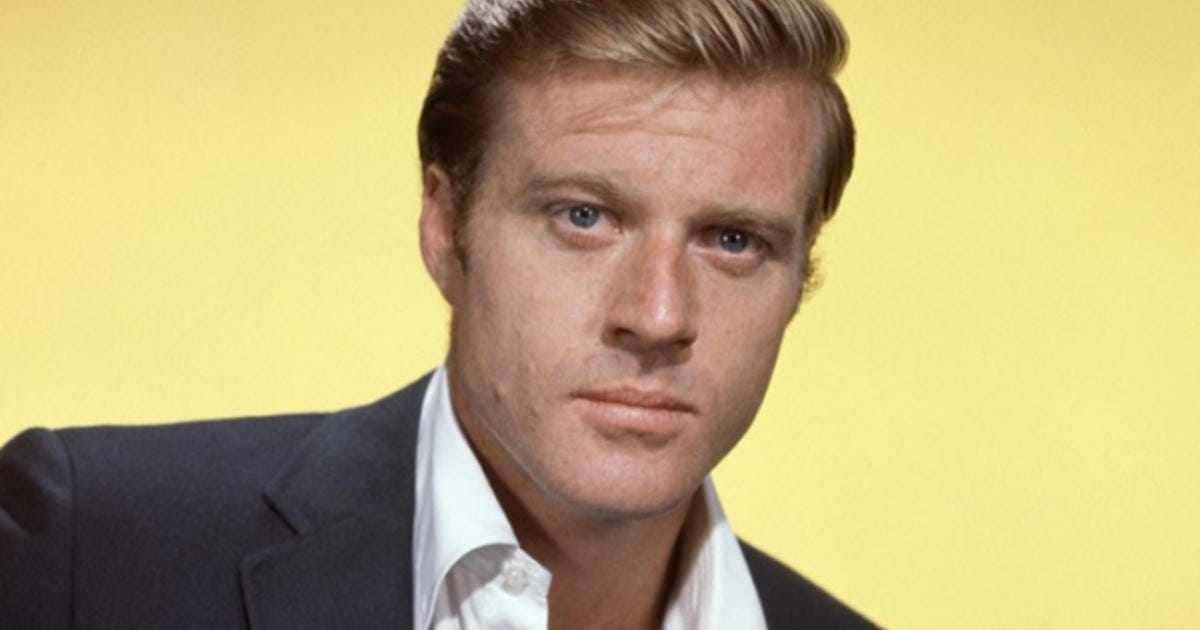

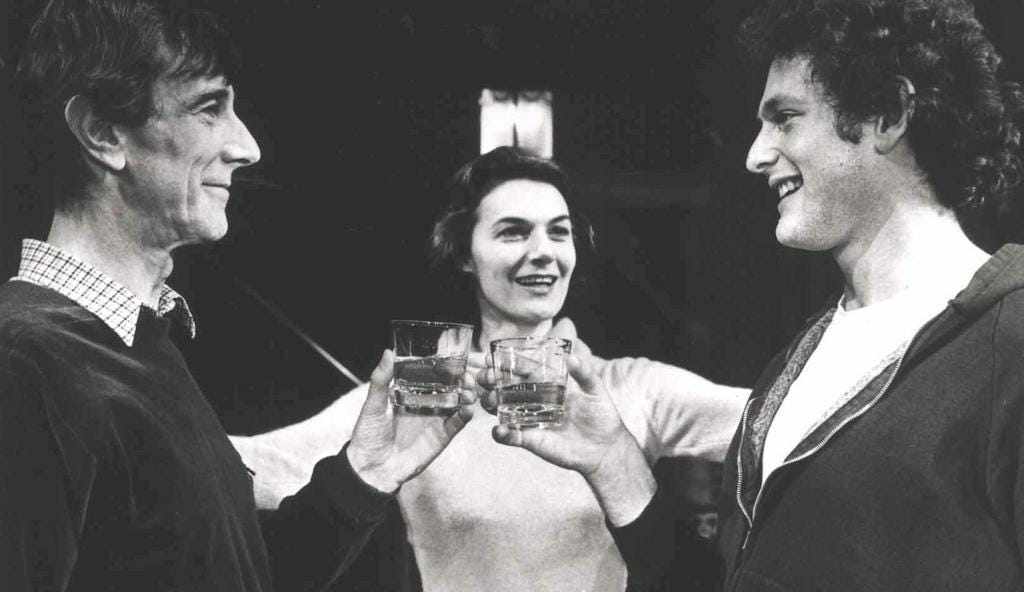

With Campanella paid off, the reliable Barry Nelson was called in. Handsome, with a deft flair for both drama and comedy, Nelson could hold his own against a host of powerful leading ladies, none of whom looked upon him as a threat to steal the show from them. Oh, he might quietly walk away with the best reviews but subversively with a wink and a smile.

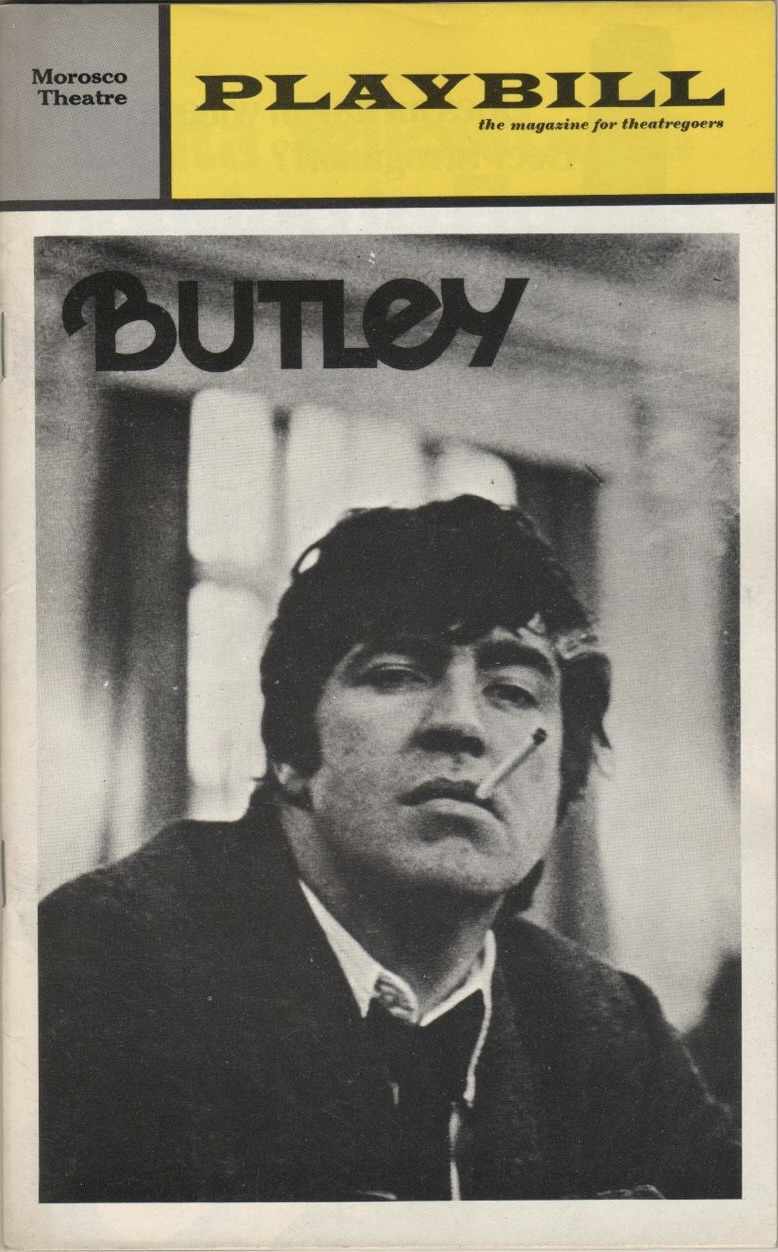

The shoe was on the other foot a few years later when Nelson found himself the one being fired. It occurred while starring in another Barillet and Gredy comedy that was adapted and directed by Abe Burrows and produced by David Merrick (so much for loyalty). Hoping for lightning to strike twice, the results with Four on a Garden were more like being caught in a torrential downpour. It consisted of four one-act plays with Nelson paired opposite Carol Channing in what would mark her only non-musical appearance on Broadway (she did a number of straight plays on tour and in stock). The playlets covered the subjects of marriage, infidelity, divorce and even murder, all taking place in the same apartment. Fine, except this was the same concept depicted in Neil Simon’s wildly popular Plaza Suite three years earlier. The plays shared the same scenic designer, too—Oliver Smith.

Similarly, Channing and Nelson donned different costumes, wigs and sometimes accents, but Plaza Suite was genuinely funny and Four on a Garden was a mess. During its nine weeks out-of-town and six weeks of previews on Broadway, there was significant rewriting with one play dumped for another and the order rearranged. When Abe Burrows found himself in trouble, the husband and wife acting and playwriting team of Joseph Bologna and Renee Taylor were brought in to help. Ironic, since Burrows was usually the one called in as play doctor. It brings to mind the story of when playwright-director George Abbott was having difficulties with a show in New Haven and offered the solution that “maybe it was time to call in George Abbott.”

Seeing that their work wasn’t making Four on a Garden any better, Bologna and Taylor refused to take any credit. Nor did the French playwrights, upon whose work it was based, who asked to have their names taken off posters and kept out of its Playbill. This was done, though no one checked Burrows’ bio in which it is mentioned that the play marks Mr. Burrows’ “third association with the material of Barillet and Gredy.” Burrows was stuck with the full credit and the poor reviews.

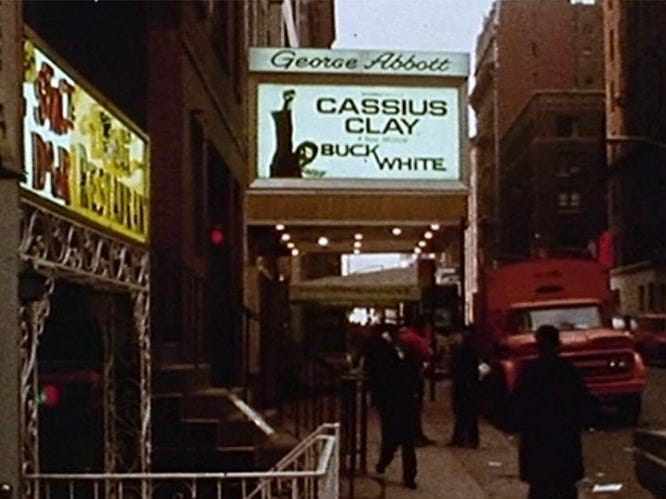

The four playlets were a prime example of something that should have closed before it reached Broadway. It was odd Merrick chose to bring it into town as he rarely shied from closing things when they couldn’t be salvaged. Perhaps he decided to roll the dice because it was doing such strong business on the road as Channing was extremely popular across the country wherever she went. However, by coming to New York, the play did allow a second chance for a young actor to appear on Broadway again. Tom (later Tommy) Lee Jones had made his debut in John Osborne’s A Patriot for Me (1969), which had run only 49 performances. Four On a Garden ran a lot longer—57 performances.

The day before Thanksgiving, 1970, Variety reported that “despite script and casting difficulties (Sid Caesar will soon take over for Barry Nelson in the show), Four on a Garden racked up $79,329 in Washington, a new house record for a straight play.” It appeared that audiences didn’t seem to care about its trials and tribulations, paying good money to see it anyway.

Getting dismissed in D.C. was the first time Nelson had to deal with being fired, which he discussed a few years later in a 1974 television interview: “That’s the only experience I’ve ever had that way and having a long career in the theatre, I must say it never is a pleasant one leaving a company, and so forth. It’s a highly traumatic experience. They brought in Sid Caesar ‘cuz they changed the play and it’s quite often how they handle it, you see. In this case no announcement was made as to why that change was being made, that they were bringing in other authors to rewrite and tailor the work in a different way and as a result, I rather resented that and challenged them on it and they had to pay me . . . I had done my job, I turned down other plays and it was not very late in the season, this is what I do. I’m a professional actor and I don’t think they should make their problem my problem. Carol Channing, as it was played originally, I thought was excellent. That she was out of character, she was away from the image that the Carol Channing fans wanted I think . . . When they found that not working they decided to go back to the image and do it in a revue-type sketch thing with Sid Caesar . . . with the German accents and things like that which is not my long suit.”

Four on a Garden tried out in five cities (New Haven, Boston, D.C. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh). It started previewing on December 21, 1971 at the Broadhurst Theatre, which was where Sid Caesar had his first great success in the revue Make Mine Manhattan almost exactly twenty-one years to the date. What followed were six essentially uselessweeks of previews, finally giving into the inevitable and inviting the critics on January 30th. I saw it on January 9th as a thirteen-year-old while changes were still being implemented. In my review, I called it “an old ladies’ comedy.” My apologies to old ladies then and now.

When the professionals came, Clive Barnes in the New York Times didn’t disagree with me. “Without Miss Channing and Mr. Caesar this would be a deplorable evening. Even with Miss Channing and Mr. Caesar it is a deplorable evening.” And Brendan Gill in the New Yorker called it “a grisly event.” It closed less than two months after opening. A short time later, Sid Caesar starred in a Chicago production of Plaza Suite’s three playlets. It’s entirely possible someone had the idea while watching him in Four on a Garden. If the show had run longer, Barry Nelson’s run-of-the-play contract would have guaranteed him a steady income. And even though the money he was due for its shorter run didn’t amount to much, it still took some serious arm twisting to get it. As Nelson said, “I had to go through a whole year of arbitration as a result of it because we had a producer who was particularly knowledgeable on the law and how to use it.”

Fun fact about Barry Nelson: he was the first actor to ever play James Bond. It was in Casino Royale on a 1954 installment of the anthology television series Climax (he played him as an American).

Ron Fassler is the author of Up in the Cheap Seats: An Historical Memoir of Broadway and the forthcoming The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns when they break, please hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...