December 25, 2024: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler.

It’s odd that I hold one Christmas memory that is like no other. First, it came after Christmas, but it was as joyous as any present that might have arrived on December 25th. It came about in 1991 inside the Henry Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles on a hot January day at a Wednesday matinee where I was magically transported for a 100 minutes to Christmas 1975 in New York City. Scenic designer David Mitchell’s delicious Upper East Side apartment, with its large picture windows that showed off a majestic view of the East River made nighttime Manhattan come alive, completed by a well-decorated tree that dominated the stage. The play was Jay Presson Allen’s Tru, a one-man drama that, by the time I caught up with it, had just ended its year-long Broadway run and was on a long national tour. Its subject matter, the writer Truman Capote, was miraculously portrayed by Robert Morse, an actor of incomparable talents that served to resurrect his once renowned career. When I walked outside into the sun-drenched street on Hollywood Boulevard, it hit me that what I had just seen was something I might never see the likes of again. And over the past thirty-plus years, it came to be, well . . . tru-ish.

Allen, who also directed, chose to set the play when recently published advance excerpts in Esquire Magazine of Capote’s upcoming new novel Answered Prayers had been met with stunned silence from his closest friends, many of whom appeared in thinly-veiled portrayals. All felt betrayed by his revealing intimate conversations, But as Capote asks in the play, “Didn’t those people understand they were talking to an artist? Isn’t all fair in war and art?”

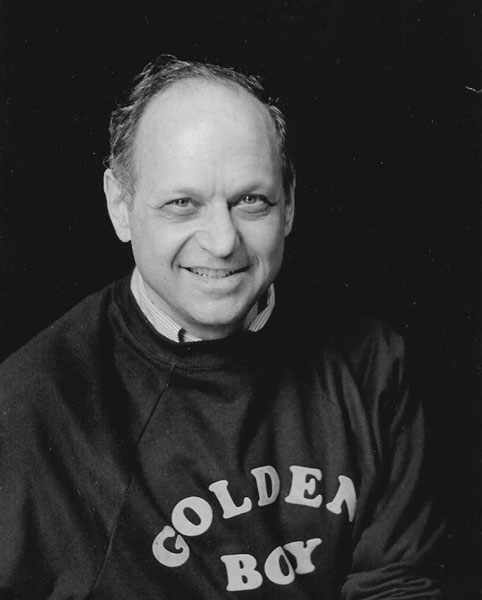

In spite of being a fine and successful writer, Capote led a tortured life, made worse by addictions to alcohol and pills. What Allen captures in her play is Capote’s voracious wit, and although often drenched in self-pity, the voice that emerges is more than just the ramblings from your average unreliable narrator. As proof the play wasn’t only Morse’s triumph, it has had a life beyond its original production, allowing for other actors to showcase their ability to channel Capote. But for Morse it was a singular sensation; one that came after many long years in the theatrical wilderness. As he described the issue he had faced for a number of years as an actor: “You want to move into character parts and it’s very difficult because people know you as that boyish Bobby Morse.”

Interestingly, the role was originally meant for someone else: composer/singer and sometime actor Paul Williams, who shared an Oscar with Barbra Streisand for “Evergreen” and also wrote “The Rainbow Connection,” among many others. At 5'2,” he made perfect sense to play the 5' 3" Capote. But when the creative team was faced with his backing out of the production, Jay Presson Allen and casting director Pat McCorkle were coming up empty with appropriate replacements. Finally, in exasperation more than anything else, McCorkle said, “What about Robert Morse? He’s short.” Not, “Hey, Robert Morse is a hell of an actor who hasn’t had the chance to show what he’s capable of for years.” Later, Allen would remark: “Comedians do the hardest thing there is . . . it’s a lot easier for them to make the transition into drama than the other way around . . . I needed someone who could take the stage, grab an audience by the nape of the neck and give it a good shake. As a musical comedy performer, Bobby is used to doing that.’’

Thus, Morse found himself with the second greatest part of his career. Before returning to Broadway, his last show, the musical So Long, 174th Street, had closed thirteen years earlier after sixteen performances. Not only was it a bomb, but the Harkness Theatre where it played, was torn down shortly thereafter. As Morse told the New York Times, “It was Kafkaesque. It was the end of the theater. It was the end of me. You get a little insecure.” For Tru, he won his second Tony (becoming one of the tiny handful of people to win for leads in a musical and a play) and when the play was taped live in its Chicago production for PBS’s American Playhouse in 1993, he won the Emmy as Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or Special. What Morse did was not so much imitate Capote’s high-pitched, lisping sound, but suggest it by way of his indelible persona, which made it completely his own. Almost unrecognizable under latex jowls and a fake double chin courtesy of makeup design by Kevin Haney (wig by Paul Huntley), it was also Morse’s idea to dramatically rip it off during the curtain call, which did not please his director. “Jay hated my doing that,” Morse told me. “But let me tell you: it worked. The audience went wild.”

And though he knew a great part when he saw one, it sill terrified Morse early on, what with the burden of memorizing a one-man show. At the point when the play was being readied, Morse had most definitely stumbled a bit. He was fifty-nine, living in Los Angeles, and employed in whatever regional theatre jobs he could find, along with the occasional TV or voiceover gig. To say it was hardly fulfilling for an actor of his talent and resume is to understate it. So when the offer came, Morse knew it had the potential to change his fortunes, but he also had serious doubts he was up for it. By the time rehearsals started, Morse realized “I’m the only one. It wasn’t like you could say, ‘Time out. Will you work with the dancers while I relax?’”

It went deeper than that. Confessing in a New York Times interview around Christmas of 1989, prior to the show’s opening on Broadway, he said: “All your life you have these little secrets . . . you wonder if you will ever get a dramatic role that touches every part of you. It was the first time I’d been afforded the opportunity. I didn’t want to fumble it.’’ And during the play’s tryout at Vassar College in July of 1989, Morse worked as hard as he ever had in his life, with the payoff being a booking at the Booth Theatre and an opening night the week before Christmas to reviews that overwhelmingly praised his performance. In the spring of 1990, he won the Tony Award over Dustin Hoffman (The Merchant of Venice), Charles Dutton (The Piano Lesson) and Tom Hulce (A Few Good Men), his speech one of the most joyous in the history of the televised broadcasts. And what irony that Matthew Broderick is present on stage, as he would go on to play Finch in the first How To Succeed Broadway revival five years later.

After Tru, it wasn’t until 2007 when the third act of Morse’s career began with his role as Bertram Cooper on the award winning AMC-TV series Mad Men. His casting always felt like somewhat pre-destined, what with his background as J. Pierrepont Finch of the Worldwide Wicket Corporation in How To Succeed in Business Without Really Trying, but it wasn’t actually the case. As series creator Matthew Weiner told the Wall Street Journal in 2008: “We mostly wanted unknowns in the cast. I felt that Robert was too famous, and I also didn’t want to be winking at the audience. But when he read for us, I thought ‘this is a great actor.’ He’s one of those performers like Christopher Walken who has such a peculiar cadence and such a naturally strange take that you never know what it’s going to sound like, but you know it’s going to be real. Everything I give him he hits out of the park.”

Once again, by sheer talent, Morse slipped into another remarkable role. “My first day I went on the set,” he recalled, “I thought I’d walked into the road company production of How to Succeed.”

As things happen in life, about a seventeen years ago, Morse’s young daughter Allyn became best friends with my daughter Charlotte while both were in high school. As a result, suddenly I got to know this wonderful guy who became a dear and most cherished friend until his death in 2022. Among the wannabe actors of my generation, I wasn’t alone in growing up with a touch of hero worship where Morse was concerned. When at age eighteen I got cast as Finch in How to Succeed, I got to take on his defining role—and believe me, I needed little preparation as I’d already committed the words of every song to memory. There’s no question his career during the 1960s and early '70s was one I dreamed of carving out for myself. That dream may not have been entirely fulfilled, but look what I got instead:

On the day I officially interviewed him for my book Up in the Cheap Seats, he arrived at my house in Los Angeles where I met him in the driveway. Although we had become friendly by this point, I had to level with him. With emotion, I blurted out to him, “Bobby, I don’t know where to begin to tell you what it means to me, after all the years I spent as a kid in my bedroom on Long Island singing along with you on the How To Succeed record, to have you to my home today.” He gave me a big hug, and later on, after we’d exhausted a great deal of talk about his sixty-year career, this quote from him is the one I most cherish, taken verbatim from the tape I recorded:

“You have just floored me with this information. I mean I go around pretty fucking depressed most of the time. It’s lonely at the top [laughing]. But what you’ve regaled me with—this conversation—has buoyed me up! It’s touched me . . . and it’s going to last at least an hour!”

The subtitle of this column is one I chose hoping to intentionally stir up memories of a story written by Truman Capote that was adapted nearly sixty years ago into a TV special. A Christmas Memory aired in 1966 on ABC and starred Geraldine Page in a performance that won her an Emmy Award. How good was she? Well, her competition was Mildred Dunnock (Death of a Salesman), Shirley Booth (The Glass Menagerie) and Lynn Fontanne and Julie Harris (Anastasia). All plays adapted for television—the good old days. It’s available on YouTube for anyone curious. Best of all: it only runs 50 minutes. Enjoy.

Ron Fassler is the author of the recently published The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns when they break, please hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...