The definition of a theatre critic has been derided for centuries as "the man who rides down the hill after the battle and shoots the wounded.” I've a few things to say on the subject (I'm a critic myself) in today's "Theatre Yesterday and Today."

When I began this blog four years ago, I made clear that I would offer opinion, but not considering myself a critic, I pledged not to review plays or musicals. I kept up with that... until two years ago when I was offered to write entertainment criticism for the website TheatrePizzazz.com. Prior to accepting the offer, this was never a profession I had any interest in. My biggest fear was the question of who am I to tell writers, many of whom are more talented than I could ever hope to be, that on some particular occasion they didn’t pass muster? Why should my opinion matter at all when it's audiences that always have the final say? Certainly there have been shows for which critics toss bouquets, only to find they never land in a vase (as it were) and flower with an audience. If no one goes, a play closes—end of story. For a myriad of reasons, I have always had my concerns about what a critic’s role is and, more importantly, what it means to the creative process. Happily, I've taken my role as critic at TheatrePizzazz to be more of a cheerleader than a scourge, which sits much better with me.

When master playwright Edward Albee died in 2016, his obituaries raised the point of what a critic’s responsibility is to the artists they cover. Albee was one of our greatest who was beaten down time and again by critics who told him, in no uncertain terms, that he was no longer relevant; that he had lost his talent and that he should pack it in. The same was said of Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams in their lifetimes. They had to suffer the brickbats delivered upon them which was both debilitating and painful. Williams never got over it, while Miller started premiering his shows in England, where his reputation hadn’t suffered as much diminution as it had here.

Albee put it succinctly and defiantly when he once told the New York Times that “Some critics are just morons by nature. Others are there to save the audience from any interesting experience.” Delving deeper and more profoundly (but no less acerbically) he said: “It is not enough for a critic to tell his audience how well a play succeeds in its intention, he must also judge that intention by the absolute standards of the theater as an art form.” As the Times noted, “He [Albee] added that when critics perform only the first function, they leave the impression that less ambitious plays are better ones because they come closer to achieving their ambitions.”

Albee went on to suggest that “perhaps they are better plays to their audience, but they are not better plays for their audience. And since the critic fashions the audience taste, whether he intends to or not, he succeeds each season in merely lowering it.”

I think that is as profound as it gets. And I don’t mean to say that it isn’t perfectly fine to have an opinion. I saw some of the titles that came and went quickly from these otherwise brilliant playwrights when they weren’t firing on all cylinders, and it was both tough and depressing. As but one example, there was Tennessee Williams’s Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald drama Clothes for a Summer Hotel, which played a week on Broadway in 1980. It was incomprehensible, boring, poorly acted and made me thankful that it wasn’t my job to report on it to a readership to which I was beholden. Though it didn’t bother Walter Kerr any, who in his review in the New York Times wrote: “The finest playwright of our time has spent his evening trying hard, much too hard, to sound like other people. People out of books. Clothes for a Summer Hotel is Tennessee Williams holding his tongue.”

I felt the same way and couldn’t possibly recommend the play to anyone, but guess what? There were probably people that saw it and enjoyed it in ways neither Kerr nor I could have comprehended. The case is also true in the reverse. While doing some research for something else, I came upon this letter “To the Drama Editor” in a New York Times Sunday Arts & Leisure section from more than 60 years ago:

I really don’t know where to begin with this critique. The Music Man may be a lot of things: corny, predictable, even a bit too precious. But boring? Unpretty costumes? Dull music? For those that know me, it is no secret here that Ms. Hand was picking on my favorite musical. She got to see Robert Preston and Barbara Cook in their prime, so yes I’m jealous she saw it, and pissed off she couldn’t appreciate it, both at the same time. I'm sure there are those who, after paying whatever they did for the impossible-to-get tickets to Hamilton, were quick to dismiss it with a wave of their hand as overrated.

Almost no play or musical can claim unanimous raves, not even Hamilton. One critic, who saw it Off-Broadway in February of 2015 wrote: “This new musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda may be many things—or, more accurately, it may be too many things—but exciting is not one of them.” (I withhold this critic’s name for his own safety).

There are naysayers everywhere. Funnily enough, Rotten Tomatoes, the website that aggregates film reviews from all over, actually boasts a number of films with a 100% rating, sometimes from over 100 critics. These high numbers are reserved for titles like The Wizard of Oz (I mean, who doesn’t like The Wizard of Oz?), but it brings up the point whether theatre sometimes divides more than it conquers. I can’t explain it. Perhaps it’s because theatre tickets have always cost more than going to the movies, so there is more at stake for an average ticket buyer. But boy, opinions sure do run the gamut.

And at the end of the day, everyone’s a critic.

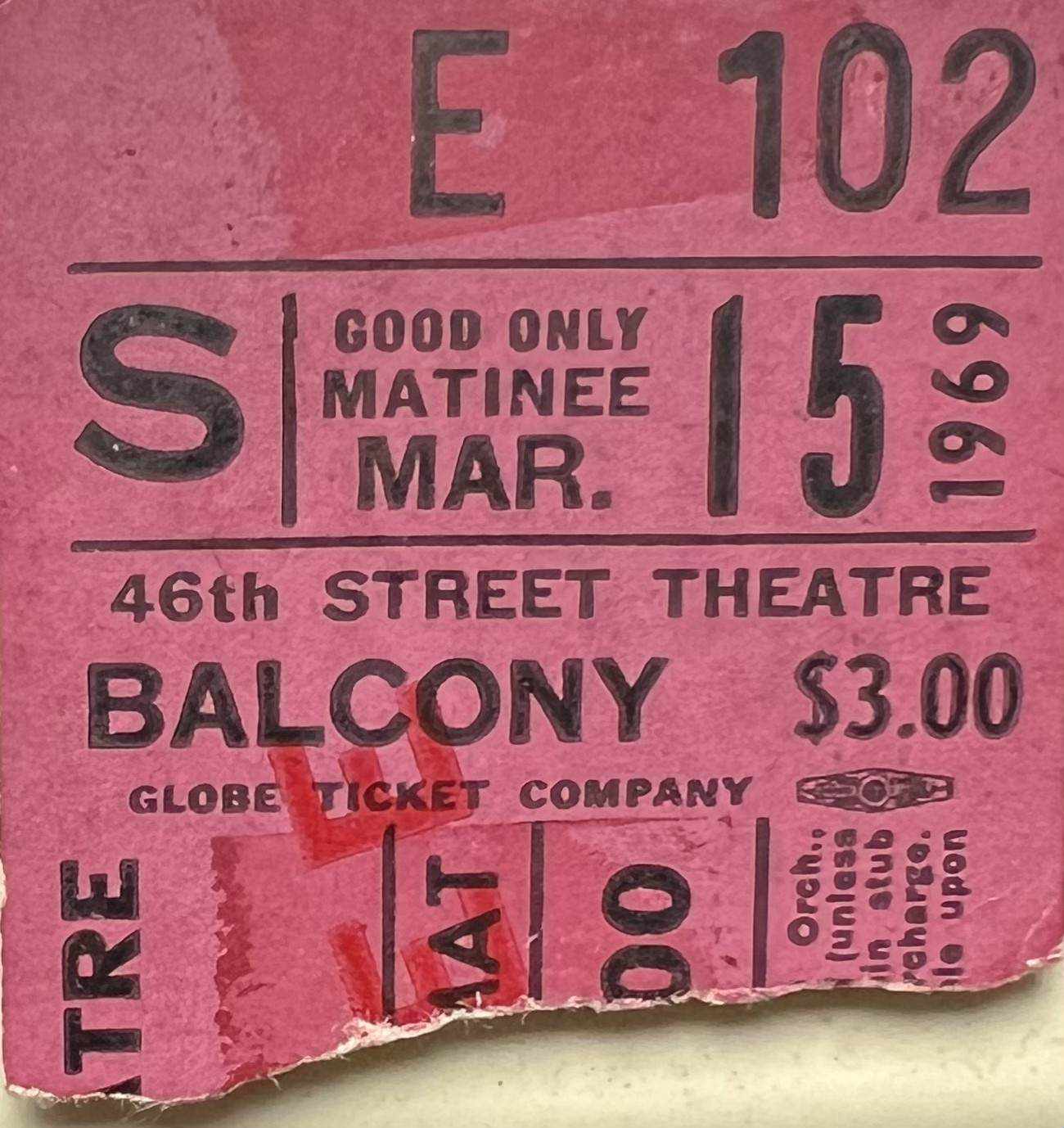

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. Also sign up to follow me here, and feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...