Called “the most original of all of us’’ by George Gershwin, composer Harold Arlen was a master of the blues and jazzy rhythms of Harlem and the south. Songs like “Blues in the Night,” “Stormy Weather,” “That Old Black Magic,’ “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive’’ and ‘’The Man that Got Away," are only five of the five hundred to which he is credited. So how did Hyman Arluck, the Jewish son of a cantor in Buffalo, New York come to be one of the most important contributors to the Great American Songbook? Read on in today's "Theatre Yesterday and Today."

I'm two days late for the 116th birthday of Harold Arlen (born Hyman Arluck on February 15, 1905), whose compositions for film and theatre endure to this day. It was his belief that songs didn't so much as flow out of him as given to him — a gift from God — which makes sense, what with him being the son of a deeply religious man. According to biographer Walter Rimler, “it was his job, once the main idea came, to work hard on them, to make them as good as he could. But the initial idea, he believed, came from some other place.” As one example, Arlen was stuck when it came time to write The Wizard of Oz's major ballad, and it was only while driving down Sunset Blvd. in Los Angeles, with his wife behind the wheel, that he told her to pull over.

“Out of the blue came the entire melody,” Rimler states. “He always kept with him a sheet of music paper that he called his jot book. He pulled it out. He had a pencil. He wrote it down. And we have 'Over the Rainbow' as a result.” Arlen later said it was the automobile horns in heavy traffic that gave him the inspiration.

As a Jew in Buffalo growing up in a mixed neighborhood, Arlen was drawn to jazz and gospel music. He played piano at a local burlesque house while still a teenager and competed at amateur nights with his original material. By his early twenties, he had already gotten his first song published. Only this did not please his parents. A family friend, Jack Yellon (who wrong the song “Happy Days are Here Again,” among many others), was invited to “talk sense” into the boy. After hearing Arlen play, Yellon delivered the sobering news to the cantor: his son was going to be a musician like his old man — “just different music.”

Dropping out of high school, Arlen went to New York City to ply his trade as a songwriter. He found the creative atmosphere of Harlem, specifically the music coming out of the Cotton Club, most hospitable to his sensibilities (he would eventually become the club's staff composer). By age twenty-five, while mostly serving as an accompanist, he was also steadily writing his own songs. It wasn't long before he struck it big with “Get Happy,” an instant popular hit.

Over time, his surging rhythms had him tailoring songs in films and stage musicals for great African-American artists like Ethel Waters and Lena Horne. With St. Louis Woman, which opened on Broadway in 1946, Arlen’s keen ear provided astoundingly great musical numbers for the all-African American cast, and they found their perfect match in the engaging wordplay of lyricist Johnny Mercer, a native son of Savannah, Georgia. Among the songs they wrote for the show were “Anyplace I Hang My Hat is Home,” “I Had Myself a True Love,” and “Come Rain or Come Shine.”

Second only to Irving Berlin in the number of credits listed in the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers Biographical Dictionary, his 1986 obituary in the New York Times claimed that more than 35 of the 500-odd songs whose music he [Arlen] wrote had become what musicians call ‘standards’— that is, pieces of music that the musicians retain in their repertories year after year.” And what sort of standards? In addition to the ten already cited, how about these additional five? “I’ve Got the World on a String,” “It’s Only a Paper Moon,” ‘’Let’s Fall in Love,” “One for My Baby” — even “Lydia the Tattooed Lady.”

There are plenty more. And Arlen had a thoroughly original singing voice (perhaps inherited from his father) which I offer here as an example of how he could sell his own tunes as well (or possibly better) than those great recording artists who continue to sing his songs:

Eight of Arlen’s first nine Broadway musicals were revues, which were popular throughout the thirties when he began writing for the stage. “Out of a Clear Blue Sky,” written with lyricist Ted Koehler, was a hit from Arlen’s very first show in the very first year of the decade: the 1930 edition of Earl Carroll’s Vanities. His first book musical the following year, You Said it did well, as did his second, produced more than a dozen years after a long stint in Hollywood. That musical, Bloomer Girl, was in partnership with the brilliant lyricist E.Y. “Yip” Harburg, with whom he’d collaborated on The Wizard of Oz. Off their re-teaming, “Right as the Rain” was added to the long list of Arlen’s prodigious repertoire.

As already mentioned, 1946 brought St. Louis Woman to Broadway, arguably Arlen's greatest score. Unfortunately, it was plagued with the wrong kind of drama necessary to produce a hit musical play. First came the death of its book writer, Contee Cullen, two days before rehearsal began (at the age of forty-three, no less), which proved a major setback. Then the bad out-of-town reviews brought in a new director, Rouben Mamoulian (coming off both Oklahoma! and Carousel), whose reputation as something of a tyrant proved well-founded. The first thing he did was fire Ruby Hill, a neophyte who had been brought in right before rehearsals started when the star for whom the show was written — Lena Horne — had a sudden change of mind. Describing Hill as a neophyte is in the truest sense of the word: she was fresh out of high school. But the cast had come to love her and Pearl Bailey, who was stealing the show, took it upon herself to unite the company in protest. On the afternoon of the Broadway opening, Bailey led a revolt that demanded Hill be reinstated or the show would not go on.

On Hill went, but in spite of raves for Bailey, the show got mixed notices. No one liked the book, and in the crossfire, even the score was dismissed. St. Louis Woman closed after 113 performances. An abbreviated cast recording featuring members of the original cast was produced, but it was incomplete. Over time, the show’s orchestrations were lost, rendering a complete recording vitally important. It wasn’t until the 1998 New York City Center Encores! that the show was roaringly brought back to life in a meticulous reconstruction, requiring the commission for a full piano score and orchestrations. The work was completed and the production, directed and adapted by Jack O’Brien, made critics stand up and take notice like they never had before. The show was one of the best realizations of the Encores! mission statement to “celebrate the rarely heard works of America’s most important composers and lyricists.”

Arlen wrote three more Broadway musicals: House of Flowers, Jamaica and Saratoga. Each was a problematic show, even if the scores all had beauties among them, with House of Flowers running a very close second to St. Louis Woman for sheer beauty and inventiveness. Unfortunately, Flowers had a terrible pre-Broadway run too, and received mixed notices. Efforts to re-work and revise it (the lyricist was Truman Capote) have gone on for years, but it’s still considered a show with a musical score far superior to its other components.

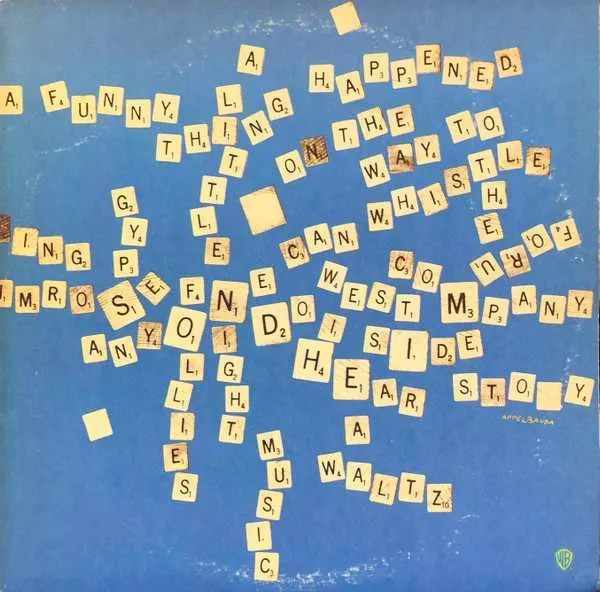

Arlen didn’t exactly retire, but slowed down his workload considerably, especially after the death of his wife, who he mourned deeply. He also had to care for her, as she suffered from debilitating depression, which due to a dependency on alcohol, afflicted Arlen as well. With his old pal Harburg, he was lured into writing the songs for a 1962 cartoon musical, Gay Purr-ee, for their mutual friend, Judy Garland. It was at this time that another female song stylist found in Arlen a kindred spirit. Barbra Streisand delved deeply into the great man’s songbook and sang his songs on each of the first three of her wildly successful albums. In 1966, his wonderful singing voice can be heard on an album which brought them together with a tongue-in-cheek title, seen here below:

Out-of-print for decades, it is now available for streaming. Listen to it for Streisand, of course (only two songs), but revel in what a fine singer the cantor’s son was. And what a fine artist. As his frequent collaborator, Yip Harburg, said of him: “His songs live. His songs seep into the heart of a people, a nation, of a world — and stay there.”

If you enjoy these columns, check out Up in the Cheap Seats: A Historical Memoir of Broadway, available at Amazon.com in hardcover, softcover and e-book. And please feel free to email me with comments or questions at Ron@ronfassler.org.

Write a comment ...