September 16, 2025: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler.

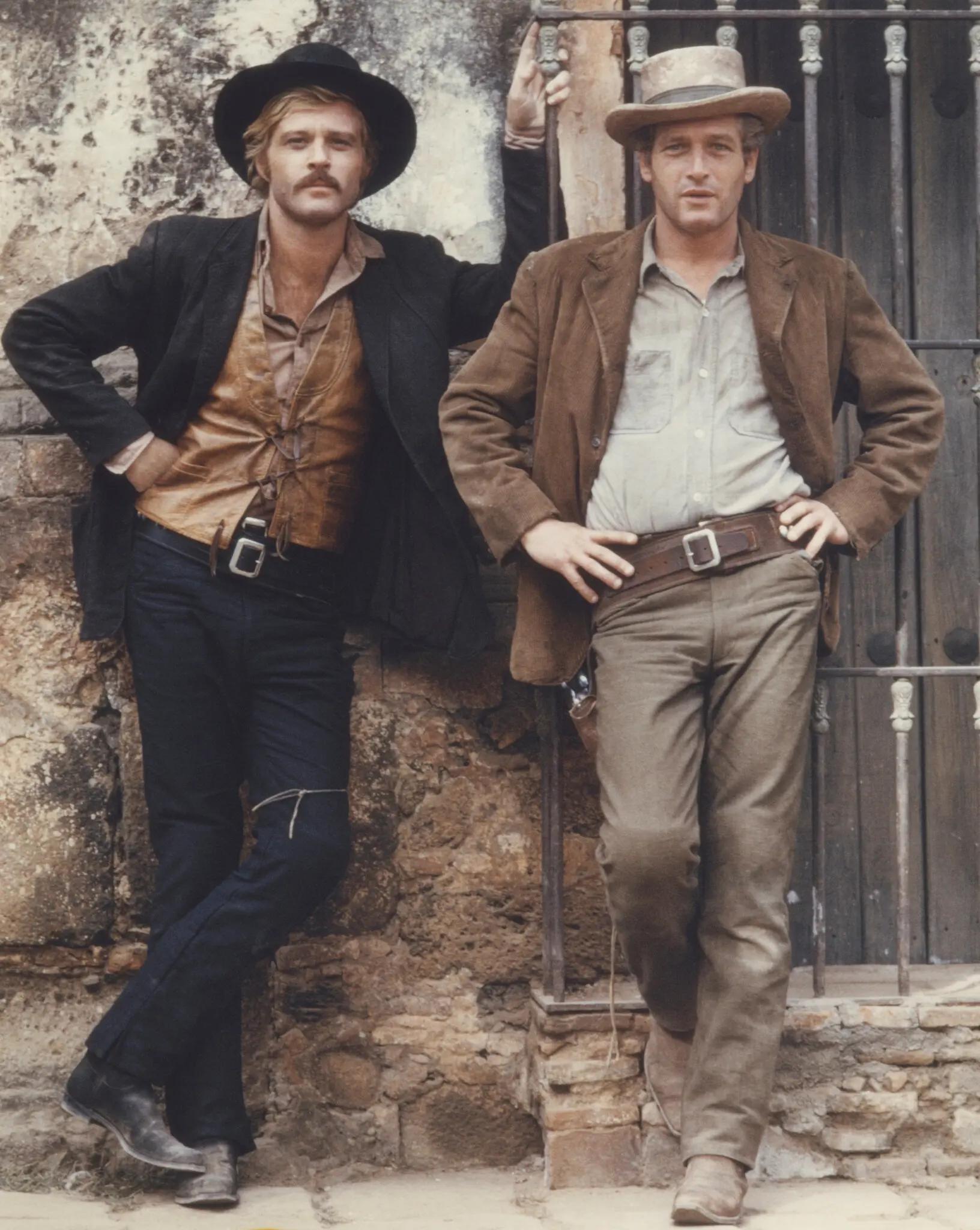

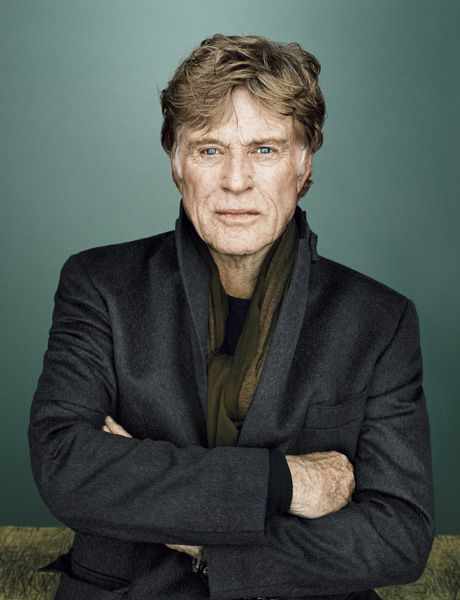

Robert Redford died early this morning at age eighty-nine. A major film actor, his star never dimmed once he burst forth onscreen in his breakthrough role as the latter of the infamous duo in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). A director, producer, activist, environmentalist, philanthropist, conservationist—a whole lot of “ists” throughout his long career (his work as an environmentalist could easily fill an entire column). There's no doubt his passing will inspire articles on his legacy, but I'm betting few will cover in depth his path to stardom which began in the theatre. It is pretty much forgotten that Redford was once an eminent leading man on Broadway. And not just any leading man, but one with enormous promise, who many pinned their hopes on his continuing in the theatre.

However, like Bogart and Brando before him (to name just two), Redford was a Broadway actor who, once the movies beckoned, never returned to the theatre. It’s a shame, considering that those who saw him in Neil Simon’s Barefoot in the Park — which definitively established Redford’s stage credentials — remember him as an actor of easy charm and effortless style. When he spoke with William Goldman for his landmark 1969 book about the theatre, The Season, Redford expressed his feelings on which road to take at that point (New York or Hollywood). Born in Santa Monica, California, Redford said, “I didn’t spend the years I spent in New York so I could end up acting in Hollywood. But in every script they’ve sent me, you could just feel the critics getting ready to roll over and play dead for the girl. All the guys end up doing is looking at her with his hat in his hand and saying, ‘You’re wild and you’re mad, and I love you.’”

As an expert light comedian, he had ambivalent feelings about what it all meant. Post-Barefoot, he wound up carrying water for actresses like Natalie Wood in films like Inside Daisy Clover and This Property is Condemned. But once his stardom was established with the Sundance Kid (with posters of him in hat and mustache that sold into the millions), Redford was poised to call his own shots. His choices were, for the most part, exemplary. Producing a number of his own films showed off not only his good taste, but an unusual prescience. He had the foresight to contact the two young, hotshot reporters from the Washington Post early on while they were still covering the break-in at the Democratic National Party’s Watergate offices. Before Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein even conceived or wrote All the President’s Men, Redford had nabbed the film rights to their story. Not only did Redford star as Woodward (opposite Dustin Hoffman’s Bernstein), but the film was nominated for the Academy Award as Best Picture. Four years later, he would win an Oscar, not as a producer or actor, but as a director, for his very first effort, Ordinary People.

It all worked better than according to plan for Redford (if there even was a plan). When Redford first started out on this thing called acting, he really didn’t know what he wanted. He had mixed feelings about his looks, something that still irked him as late as 2013, when an Esquire journalist reported in print: “Not his favorite subject, the face. [As a young man] The car got him out of Dodge; the promise of a baseball scholarship got him to the University of Colorado, where the booze helped get him tossed; painting took him to Paris and Italy, acting to New York City, where he attended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and began working on Broadway and television. But it was that face that made him a matinee idol and held him hostage.”

The writer has an interesting point. It’s hard for most people to imagine what an actor, trapped by his good looks might feel like. When you’re ambitious and have things to say, it can make it hard to be taken seriously if you are dismissed as “just another pretty face.” For that reason, the self-destructive streak referred to (i.e. his getting tossed from school) lingered for some time, as Redford described not long ago to New York Magazine: “That point in my life [going into Barefoot] was kind of a dark period. I wasn’t sure I wanted to act. I decided, I’m gonna sabotage this, I’m gonna make them fire me. I purposely didn’t learn lines — just really perverse stuff. Somebody else would have just let me go, but Mike Nichols [Barefoot’s director] said, ‘You’re gonna be in the play no matter what. You can just lie down on the stage, but I want you to be in the play.’ Had I really won, it would have been a disaster. What a risky thing for Mike to do … I let out a lot of rage in improvisation, and through a craziness I discovered I had when onstage. It was like working with a therapist, that time with Mike, but at least you knew the therapist was a little nuts.”

Nichols helped Redford in a number of other ways, one of which was his use of humor in dealing with situations. “It was Mike’s first job directing a play,” Redford recalled. “How he dealt with his nervousness had a lot to do with his sense of humor and his intellect. On opening night, he pulled the cast backstage and said, ‘Don’t worry, but just remember that everything depends on tonight.’”

Redford had nothing to worry about. Among the rave reviews he received for the Simon comedy was this one from Newsday critic George Oppenheimer: “Mr. Redford has comedy timing, lilt and reality and, as a bonus, one of the most pleasing personalities to hit the stage in a decade or so.” Prior to Barefoot, Redford had appeared in four Broadway shows. He replaced an actor in a 1959 Howard Lindsay-Russel Crouse comedy, Tall Story, then had roles in three others, the most significant of which was Norman Krasna’s Sunday in New York, the show that gave him his first solid lead (Rod Taylor got the part in the film). But Barefoot was a huge hit and cashed in on Redford’s earlier promise with audiences and critics alike. His co-star, Elizabeth Ashley, said of him: “He has a dry humor, and he can make that funnier than almost anybody, given the right material. It’s deeper than delivery; it’s a point of view.” According to a 1998 New Yorker article, its author, Richard Radnor stated that “Redford had a wild comic energy that audiences these days have never seen. Alan J. Pakula, who later directed Redford in All the President’s Men, said of him, at that time, “He had the Cagney stuff, all the rage. When I first saw him as a young man, he obviously had to fight for stability.”

Interesting how all that worked out. Redford eventually entered “grand old man” territory within the film industry, both in front and behind the camera, as a knowledgable elder statesman. It can never be underestimated what his work with the Sundance Institute, which he founded nearly forty-five years ago, did for independent film and its filmmakers. Besides the better-known Sundance Film Festival and Film Labs, there is also a Sundance Theatre Lab that has been going strong for more than twenty years. Over that time, countless artists in plays and musicals have been nurtured at Sundance in the mountains of Utah.

Through that work, even if Redford lost interest in stepping onstage, the goings-on at Sundance Theatre Lab told a different story. The first-ever workshop of I Am My Own Wife was presented there, which would eventually win its author, Doug Wright, the Tony and the Pulitzer Prize. Steven Sater and Duncan Sheik's musical of the early–20th-century play Spring Awakening, by Swiss writer Franz Wedekind, also became a multiple Tony Award winner. Other plays that made their way through Sundance include Tony Kushner's Angels in America and Annie Baker's Circle Mirror Transformation and musicals such as Grey Gardens and The Light in the Piazza.

But what Redford and company achieved so many years ago with Barefoot in the Park was a true rarity in the theatre at the time. Mike Nichols (in his first directing effort) was insistent about making the sometimes slightly-over-the-top situations in Simon's play come off seriously. No one tried to be funny, but instead, its small cast led by Redford and Elizabeth Ashley crafted artful comedy. The more they played things for real, the funnier things got. It's a shame he never returned, but for one glorious season, Robert Redford starred in the most hilarious show on Broadway.

This column was adapted from an earlier post August 18, 2020.

Ron Fassler is the author of the recently published The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and "Theatre Yesterday and Today" columns when they break, please hit the FOLLOW button.

Write a comment ...