January 12, 2026: Theatre Yesterday and Today, by Ron Fassler.

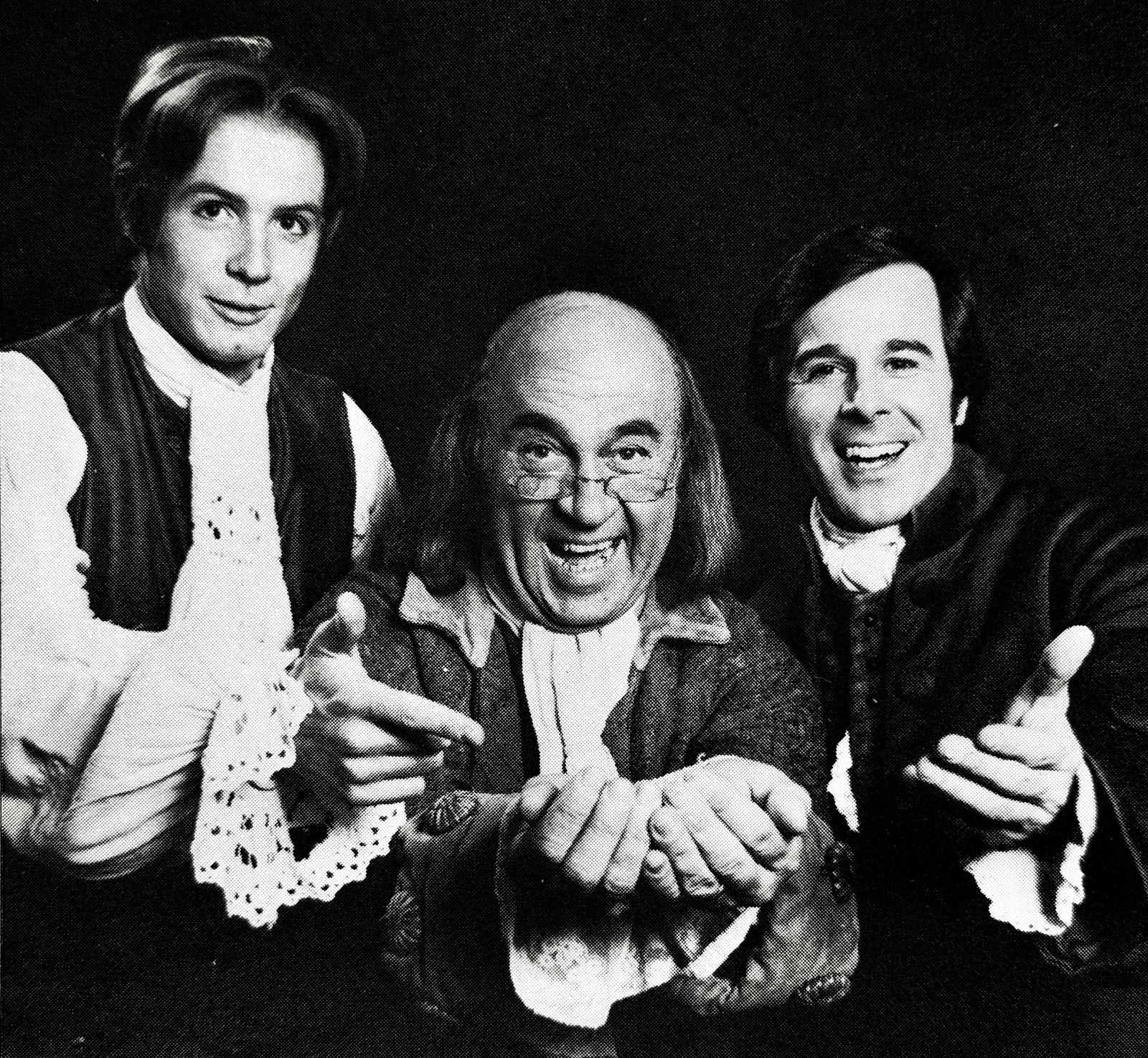

It took me a few days to talk to some people, look up a few facts, and take the proper time to write about John Cunningham, who died this past week at the age of 93. A working actor for the overwhelming majority of his sixty-year career, he was once described in the New York Times as “ever-reliable and ever-employed.” I can easily recall that during my time as a rabid teenage theatergoer how he was seemingly in a different Broadway musical every season. In 1968, he took over from Bert Convy as Cliff Bradshaw in Cabaret, in 1969, he co-starred with Herschel Bernardi and Maria Karnilova in Zorba, in 1970, he created the role of Peter in Company (eventually standing by for the leading role of Bobby), and in 1971, he succeeded William Daniels in 1776. As a fourteen-year-old, I got to know him during his ten months portraying John Adams. Though I’d seen Daniels (twice), I was so in love with the show I saw Cunningham play it ten times from out front as well from the wings backstage. The reason for that is the stage doorman liked me or at least didn’t mind my presence. Since 1776 had a nearly three-hour running time, I would wander over and catch the final half-hour following whatever matinee I was seeing that Saturday. Mensch that he was, Cunningham was one of those who took an interest in me and spent time on numerous occasions being especially kind to a stagestruck kid.

In addition to his sixteen Broadway credits in plays and musicals, Cunningham racked up more than forty off-Broadway and in regional theatre. Graduating from Dartmouth College before joining the Army, he eventually wound up stationed in West Germany and France as part of an acting troupe performing for troops. After his Army tour of duty, the GI Bill allowed him to continue with his studies and he graduated with a masters’ degree from Yale Drama School, training that led to his playing Petruchio, Mercutio, and Prince Hal in 1965 at the American Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford, CT. And, like so many stage actors back in the day, he gained substantial employment on a half-dozen soap operas (I followed him on CBS’s Love is a Many Splendored Thing). Being a New York-based actor, all were shot locally, same as his television guest star appearances which include eight episodes of Law & Order, predominantly as attorney Donald Walsh. His features number Mystic Pizza, Dead Poets Society, and School Ties, though my favorite of his film performances comes courtesy of his talents as a prolific voice-over artist. Listen to his embodiment of the “Be A Man” tape from In and Out (1997), a simply hilarious bit that YouTube generously supplies with a clip:

In the theatre, where he lived most of his professional life, Cunningham was often cast by some of the best directors in the business. Besides his relationship with Harold Prince, who utilized him in Cabaret, Zorba, and Company, he was cast by James Lapine (Sunday in the Park with George, Passion, Amour), Joe Mantello (Design for Living), Christopher Ashley (The Naked Truth), Arthur Laurents (Birds of Paradise), Dan Sullivan (The Sisters Rosenzweig) and Jerry Zaks (Six Degrees of Separation), to name but a few.

In 1960, at the very start of his career, director Moss Hart tapped him for a national and international tour of My Fair Lady. It meant that even before he had the chance to hire an agent, Cunningham had the good fortune—at twenty-seven, no less—to be cast as Zoltan Karparthy, in addition to understudying Henry Higgins.

He had his ups and downs like all actors do, sometimes doing good work in the theatre seen by far too few. I was fortunate to catch the Old Globe Theatre premiere of Into the Woods (1986) in San Diego, in which he played the Narrator and the Wolf; to my knowledge, a combination not done since. Maybe it felt wrong to portray the wolf as something of a dirty old man rather than a strapping young one, but in any event, Cunningham did not go forward with the show when it moved to Broadway. I also had great fun seeing him in the workshop of Grover’s Corners (1984), Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt’s musical version of Our Town (Liz Callaway and Scott Waara were Emily and George). Cunningham made a perfect Stage Manager, though the show never gave a strong enough reason for musicalizing a perfect play.

All actors are somewhat boxed in by their type. In Cunningham’s case, he had the solid patrician looks and manner of speech that got him cast time and again as a man of means. “I sometimes feel I’m a character actor trapped inside this WASP look,” Cunningham told Playbill in 1997. “But one cannot fight that.” When he played the upper-class, uptight father in A.R. Gurney's The Cocktail Hour, the New York Times reviewer wrote: “It is a commanding performance by an actor perhaps born to play this character.”

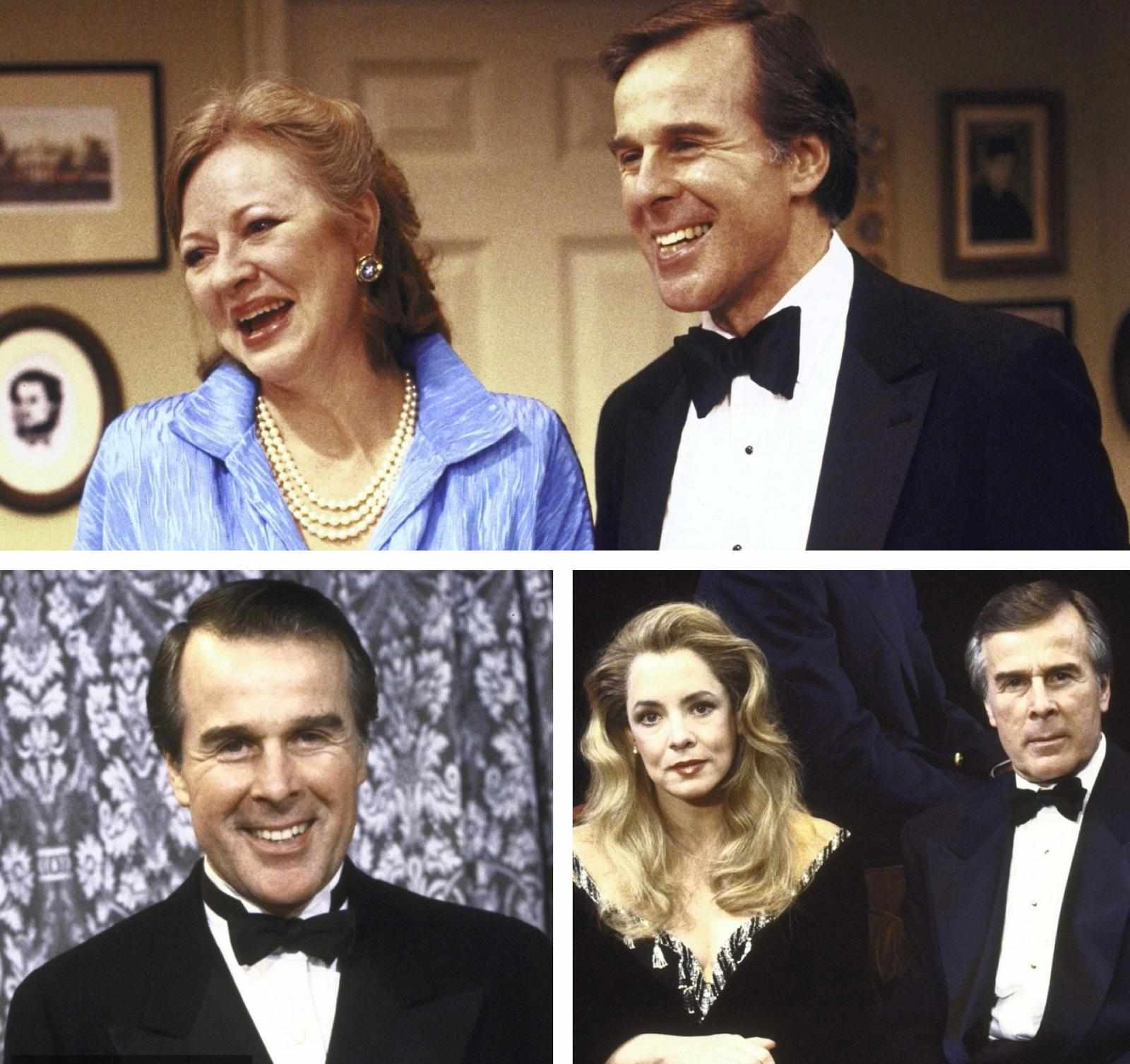

Listen, if you looked as good in a tux as he did, these were the roles you were simply born to play:

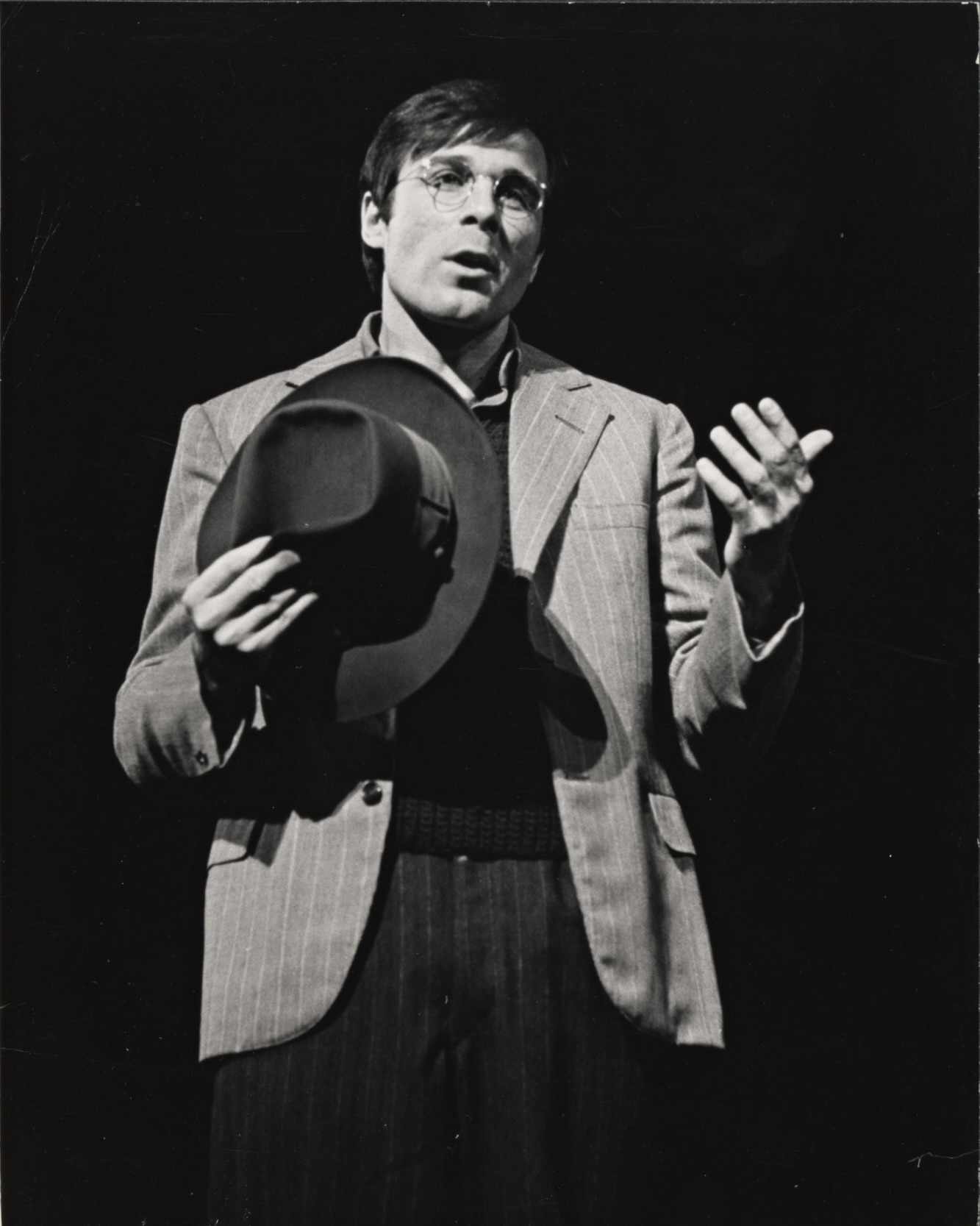

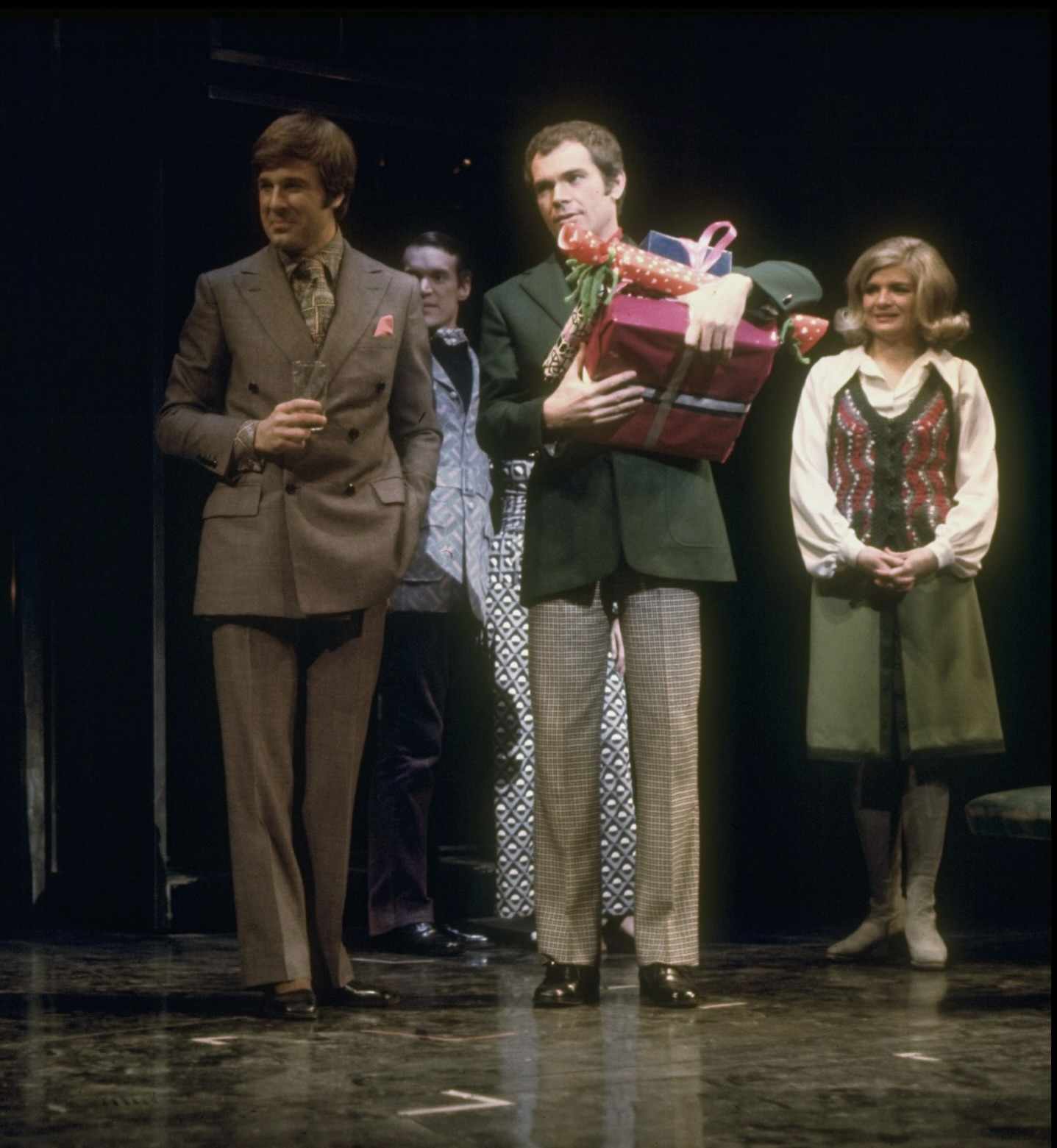

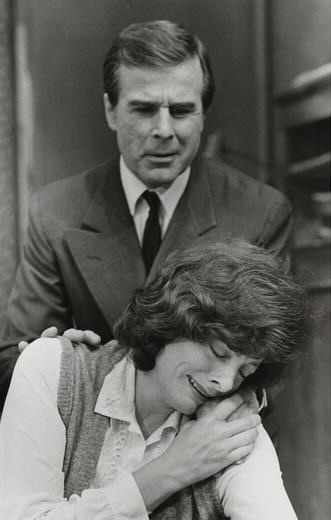

And since he was such a handsome devil, here are some more photos in chronological order:

It’s a shame there’s so little video to showcase how strong a singer and actor he was in his heyday and what his physical and vocal presence brought to each of his roles. Though take the time to listen to his rendition of “The Butterfly,” one of the most beautiful in the whole John Kander-Fred Ebb songbook. Take special note of how he handles the phrasing and intonation of “Give me light . . . give me time.”

His last play in 2012 came at age eighty, when he shared an off-Broadway stage with Kathleen Chalfant as his wife in Tina Howe’s Painting Churches. As Gardner Church, a retired poet whose increasing mental decline is in evidence, the New York Times wrote “the fear and confusion flashing across Mr. Cunningham’s face are heartbreaking.”

I was present at perhaps Cunningham’s final appearance on a New York stage. It was a 2014 one-night only reunion concert of the original cast of Titanic at Lincoln Center’s Geffen Hall and it was one for the record books. Having created the role of the Titanic’s Captain E.J. Smith, Cunningham’s participation helped make the evening a thrilling experience. Though a bit unsteady on his feet, this eighty-two-year-old veteran stood tall, evidenced by his ability to still command an audience.

Memories of the generosity of his time that Cunningham gave me when I was hanging around 1776 backstage at the Majestic Theatre have stayed with me for fifty-five years. Of course, I told him I wanted to be an actor and, like most professionals, he joked by saying, “I feel so sorry for you.”

Once, I recall standing on the corner of 8th Avenue and 44th Street and asking him, “What’s your favorite number in the show?” and his saying, “‘Molasses to Rum.’”

Staring at him in disbelief, I said, “But that’s not your song.”

“Exactly,” came his reply. “For those four minutes, Adams gets to rest.”

Another time, I told him that I had caught my little brother in my room playing my 1776 album and instead of singing, “I say vote yes! Vote yes!” my brother was singing, “I sing gorgeous! Gorgeous!”

He laughed and said that he had a similar story when he was playing El Gallo in The Fantasticks (he replaced Bert Convy who replaced Jerry Orbach). His son was old enough for the first time to see his dad onstage and when the show was over, Cunningham asked “What was your favorite thing?” And his son said, “The song about the atomic ray.”

You would have to know The Fantasticks to know how funny that it is. If you don’t, have someone explain it to you.

This passing leaves me sad; another reminder that nearly all the leading men and women I saw onstage in their vibrant mid-thirties to forties are now either in their late eighties and nineties—or dead. But how lucky was I to have found a shining example like John Cunningham to look up to; an actor who managed to have a fine career as well as a healthily, sustained home life. He was married for nearly seventy years to his wife, Carolyn Cotton Cunningham, a former Rye City Council member and long-time local environmental activist.

In that same interview, Cunningham told Playbill, “In theatre you get to do it again, and again, and again. My whole pleasure is trying to get better. So, my ritual is to take time with myself, review what has happened, prepare myself so that inspiration can happen to me in the moment onstage. Be prepared to be alive.”

Even without becoming a star, I imagine Cunningham felt richer than stardom might ever have afforded him. As his family wrote in his obituary, “He died early Tuesday morning in his beloved Victorian home aside the 11th hole at Rye Gold Club.” It’s where he and his wife lived for fifty-seven years and raised their three children, Christopher, Catherine, and Laura.

He wasn’t my friend but John Cunningham sure was friendly to a young man once upon a time. I am forever grateful.

Ron Fassler is the author of The Show Goes On: Broadway Hirings, Firings and Replacements. For news and “Theatre Yesterday and Today”columns when they break, please subscribe.

Write a comment ...